Remembering Pop Icon Claes Oldenburg (1929–2022)

Paying homage to the man behind the biggest baked potatoes of the last century 🥔 🙌

Welcome to the latest issue of Weekly Special, a food-art newsletter by Andrea Gyorody.

As soon as I saw the news last month that Claes Oldenburg had died at the age of 93, I began assembling this edition of Weekly Special. Oldenburg is easily one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, not least because of how he rendered foodstuffs with wit, charm, and a distinct lack of pretension. It’s impossible to imagine the landscape of food art (or Pop art, or sculpture) without him.

I’m sad to say I didn’t know Oldenburg personally, but I got to know his work quite intimately when I was curator of modern and contemporary art at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin, home to quite a few Oldenburgs, including his very first commissioned public sculpture, a partially buried three-way plug. Whether pulling his soft toaster out of storage, installing his plaster oranges, or watching as conservators restored the shine to the giant plug’s prongs, it never failed to put a smile on my face that we were lavishing so much care and attention on such anti-monumental, tongue-in-cheek objects. Perhaps more than any other artist, Oldenburg taught me that great art doesn’t have to be serious.

In a review of Oldenburg’s major MoMA exhibition in 2013, New York Times art critic Holland Cotter wrote, “Pop art is basically about two things: ordinariness and eating.” In the case of Oldenburg, though, I’d argue it’s more than that: it’s about finding childlike joy and delight in all of the random bits and bobs that we encounter in daily life, and then making them even more delightful for the benefit of other people.

So with that, let’s dig in!

This Week’s Special: A Tribute to Claes Oldenburg, One of the Greatest Food-Artists of All Time, Part 1 of Several

All works below are by Claes Oldenburg unless otherwise noted.

I tried to cram all of my favorite works by Oldenburg into one issue of this newsletter, but it quickly became so unwieldy with fabulous images that I decided to make this a multi-part series, to appear over the course of the next few months (likely interspersed with issues on other subjects, including my very belated and equally impossible tribute to Wayne Thiebaud). Each issue in the series will be dedicated to one or two foodstuffs, beginning today with the humble baked potato. These aren’t Oldenburg’s most famous food sculptures, but I think they should be.

THE BAKED POTATO

The baked potato as we know it is probably an English invention, but nothing says American steakhouse dinner to me (besides a whopping porterhouse) more than a piping hot potato oozing melted butter. Over the course of his career, Oldenburg made quite a few, starting with this larger-than-life spud he created in 1963.

That first potato was done in the style of the chicken wire-and-plaster sculptures Oldenburg had made en masse for his 1961 project The Store, a zany installation in a Lower East Side storefront where Oldenburg sold his work directly to passers-by who looked long enough to realize the work wasn’t mere trash. Or, really, that it was more than just garbage: it was art mimicking the detritus of everyday life encountered on the LES, complete with AbEx drips of garish enamel straight from the paint can, a parody of Jackson Pollock that, Oldenburg once said, paradoxically brought him to a sense of authenticity. "I feel as if Pollock is sitting on my shoulder,” he admitted, “or rather crouching in my pants!"1

This was a pivotal time for Oldenburg. The Store directly preceded his first uptown gallery show, in 1962, where he debuted the “soft sculptures” sewn by his then-wife, Patty Mucha. (More on her in the next issue.) A year later, Oldenburg reprised The Store in another exhibition at Green Gallery, and then he and Mucha moved to Los Angeles in time for his first West Coast show, at Dwan Gallery, where (to bring this tale full circle) the baked potato appeared on a low pedestal in a room full of soft sculptures.

It was in LA that the plaster potato found its forever home, purchased by ad exec and collector Robert H. Halff, who later donated it to the LA County Museum of Art along with dozens of other works, including this cute little cherry pastry.

In 1965, Oldenburg made this drawing of a baked potato tossed in a corner (which looks kinda like a frazzled khachapuri?), and then a year later, immortalized baked potatoes en masse as the subject of his first “multiple” — editioned small sculptures that were much more affordable than singular artworks. The potatoes were Oldenburg’s contribution to 7 Objects in a Box, an edition that included work by Allan D’Arcangelo, Jim Dine, Roy Lichtenstein, George Segal, Andy Warhol, and Tom Wesselmann. For the edition, Oldenburg fabricated 75 near-identical porcelain potatoes swimming in sour cream and chives, their russet jackets no longer dripping with gestural paint but instead rendered with an almost convincing verisimilitude.

Oldenburg returned to flights of fancy with his 1970 oversized potato, made out of canvas and topped with neat pats of (wooden) butter, a hard-and-soft combo he explored in other works as well (including the Oberlin toaster, which has wooden bread slices). I’m especially enamored of the zippers sewn into the exterior of this anemically beige spud, which make the term “jacket” winkingly literal.

The soft sculpture was also immortalized in this dramatic 1979 magazine ad for a show in Houston, which renders the spud a precious specimen to be preserved in a glass vitrine:

By 1970, when the soft potato debuted, Oldenburg had separated from Patty Mucha and was dating Hannah Wilke, a feminist artist who often depicted or invoked the form of labia in her sculptures. When she struggled with criticism, Oldenburg reportedly told her: “They’ll eventually accept baked potatoes, but I don’t know if they’ll ever, ever be able to accept you’re making female genitals—although visually they look very similar.”2

True and… true?

Anyway, Wilke was Oldenburg’s lover and studio assistant / documentarian during the years he was assembling his Mouse Museum, which debuted at the quinquennial exhibition documenta in 1972.3 The monumental installation is a cabinet of curiosities filled with cheap knickknacks alongside some of Oldenburg’s own artworks, all of which is displayed inside a squat structure shaped like a geometric mouse. Among the items in the museum are, of course, two lil’ porcelain baked potatoes.

Just One More Bite…

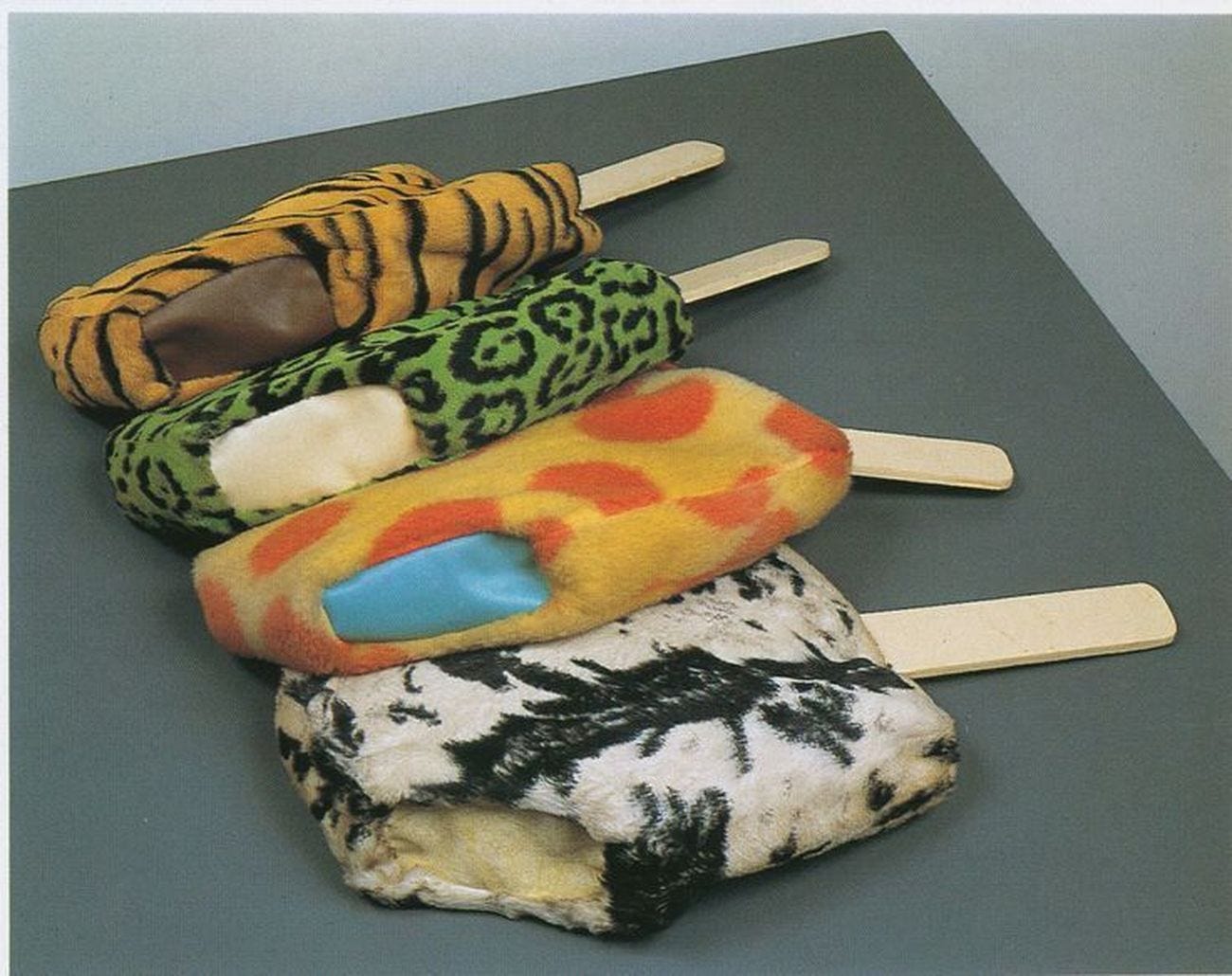

I thought about writing a recipe for a baked potato… but who wants to turn on an oven right now? So instead, I’m using this space as a way to share one more non-tuber work by Oldenburg that relates to our family’s favorite new summer hobby: making fruit popsicles.

As a way to use up the excessive quantities of strawberries and stone fruit I’ve been buying at the farmer’s market, my three-year-old son Ezra and I recently dug out our set of popsicle molds and our unread copy of People’s Pops and got to work.

Like many preschoolers, Ezra is basically a fruitatarian, so cracking open a cookbook where everything is made of fruit was a magical experience. At his insistence, we’ve made strawberry-buttermilk pops, plum pops, and cantaloupe-watermelon-yogurt pops. They’ve all been delicious, but the winner thus far is the plum, which has a deep, gorgeous purple hue and tastes through and through like summer’s juiciest stone fruit.

The recipe below, adapted from People’s Pops, is a blueprint you can use for almost any fruit-based pop, though I’ve found that some really benefit texturally from the addition of buttermilk or yogurt, which keeps the pop from becoming too icy.

Plum Popsicles

Makes 6-10 pops, depending on the size of the molds

Acquire 12 small or 5 large plums of any variety. If your plums are quite firm, you might want to cut them in half and roast them at 350 degrees for 20-ish minutes to soften them up. Or you can let them sit around for a few days to avoid the oven (or because you conveniently forgot about them, but hey, it all worked out!).

While waiting for your plums to roast or ripen, make 1 cup of simple syrup by mixing 2/3 cup water and 2/3 cup granulated sugar in a small saucepan and stirring over low heat until the sugar fully dissolves. Set aside to cool.

Once your plums are ready, plop them into a blender or food processor and blend until relatively smooth. (Pro tip: this task is kid-friendly and is likely to induce shrieks of delight.)

Add the simple syrup to the fruit purée and pulse for a few seconds to combine. You can also add just a little at a time if your fruit was especially sweet, but bear in mind that flavors dull as they freeze, so you want the mixture to wind up a teensy bit too sweet.

Pour the mixture into your molds, insert sticks, and freeze for at least 4 to 5 hours or overnight. Distract yourself with other snacks. Once the pops are fully frozen, you can unmold them under warm water and store in plastic bags or eat them straightaway.

Thank you for reading! Take a second to “like” this post if you enjoyed it, and a few more seconds to forward this email to a friend. If you want food-art content even more often, follow Weekly Special on Instagram, where I share many more tidbits than I write about in the newsletter.

Go enjoy some art and food IRL, and see you again soon!

Claes Oldenburg, qtd. in Barbara Rose, Claes Oldenburg, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1970, p. 65.

Gerrit Henry, “Art 76: Views from the Studio,” ARTnews (May 1976): 35. Qtd. in Tracy Fitzpatrick, "Hannah Wilke: Making Myself Into A Monument," in Hannah Wilke: Gestures, Neuberger Museum of Art, 2009.

Wilke and Oldenburg had a very messy falling out in 1977 that resulted in each suing the other over subsequent years, beginning with Wilke suing Oldenburg for wrongfully terminating her employment along with their relationship, and for refusing to acknowledge her contributions to the Mouse Museum and Ray Gun Wing.

Could not love this newsletter more 💓🥔