Welcome to the latest issue of Weekly Special, a food-art newsletter by Andrea Gyorody.

If you’ve landed here but you’re not yet subscribed, you can do that right now:

Before we get to our artwork of the week—I did a thing! As I mentioned at the top of the last newsletter, I was just in LA, where I installed the exhibition I Like LA and LA Likes Me: Joseph Beuys at 100, which explores how Beuys’s wide-ranging legacy lives on in the work of five LA-based artists.

The show is up at Track 16 Gallery until September 12, so there’s lots of time to see it! I will also be back in LA permanently (!!!) starting August 1, and would be delighted to meet up with folks at the gallery for a tour (or a brief look at the art followed by tacos, which is how I plan to end every art jaunt for as long as I am lucky enough to live in southern California).

Now let’s dig in!

This Week’s Special

Joseph Beuys

Friday Object “1st-Class Fried Fish Bones (Herring)” (1a gebratene Fischgräte [Hering]), 1970

Fishbone and greaseproof paper, inscribed and stamped, in glass-fronted wooden box

Edition of 25; Publisher: Eat Art Galerie, Düsseldorf

German artist Joseph Beuys was the subject of my doctoral dissertation, so it’s fair to say I know quite a bit about the guy and his vast body of work, which encompasses drawing, painting, sculpture, installation, performance, sound, and video, on top of a bazillion recorded interviews and lectures. But when I sat down to write about this weird little fried fish suspended in a box—an example of which is included in the Beuys show I just opened in LA—there were still some surprises in store for me.

Before we go deeper on the fish, though, I recognize that while Beuys is a household name in Germany (not unlike Picasso or Warhol in America), he’s an artist’s artist elsewhere, which means he’s still largely a figure of obscurity outside of the German-speaking world. So for those who need it, here’s a quick(ish) primer on Beuys:

Beuys was born in 1921 in Krefeld, Germany, and raised in the small nearby town of Kleve, close to the Dutch border. And now, rather swiftly, comes the very icky (and for some critics, insurmountable) part of Beuys’s life story: like so many other German kids of the 1930s, Beuys was a member of the Hitler Youth, and volunteered for the Nazi air force in 1940, with World War II already underway. He served as a radio operator and second pilot; during the invasion of southern Russia and Crimea in 1944, his plane was shot down, killing the main pilot and severely injuring Beuys. He was captured not long after by the British and interned in a POW camp for some months before returning to his parents’ home in bombed-out Kleve. Important side note: Many years later, around 1970, he told an interviewer that he had been rehabilitated after the plane crash by nomadic Tatars who applied wrappings of fat and felt to his body (explaining the frequent appearance of those materials in his work), but that story—which has captivated many, and still appears with great frequency in Beuys literature—has been roundly debunked by recent scholars and journalists. Beuys did crash his plane, but the miraculous Tatar rescue is pure self-mythology.

After the war ended he enrolled at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie (Art Academy), where he studied sculpture and became enamored of the philosophical writings of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Anthroposophy, a movement that emphasized freedom, spirituality, and creativity as the bases of individual growth and social well-being. Once out of school, Beuys began creating sculptures and drawings using non-traditional materials, including beeswax, asphalt, gauze, sand, dirt, and fat; he also slowly expanded his own conception of what art could and should be. By the late ‘50s, Beuys believed that anything and everything could be understood as art. In his view, even the most mundane aspects of everyday life can be invested with creativity, which is hardly the sole province of Art or Artists. The idea wasn’t original: he borrowed liberally from Novalis and other 18th-century Romantics, but he transformed their poetry into the pithy pronouncement, “Everyone is an artist,” and used it brilliantly as a tagline.

In the early ‘60s, Beuys linked up briefly with the Fluxus crowd, which inspired him to pursue performance art, but most of the hardline Fluxus figures were put off by his heavily symbolic and shamanistic performances. Case in point: one of his best known performances, Wie man dem toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt (How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare), performed in Düsseldorf in 1965, consisted of Beuys, his face covered in honey and gold leaf, walking around a gallery exhibition of his own work whispering to a dead hare cradled in his arms (and occasionally held between his teeth), while the audience gawked from outside the gallery’s giant front window.

That same year, Beuys started to produce multiples, small objects released in varying edition sizes, at the urging of an enterprising young dealer in Berlin named René Block. As Beuys had become more ambitious and conceptual and political in his work, he saw multiples as a way to transmit his message—cryptic though it might have been—far and wide, and at a relatively low price point.

That brings us, finally, to Friday Object “1st-Class Fried Fish Bones (Herring).” The work you see below is one exemplar of a multiple made in an edition of 25, which means there are 25 more or less identical versions of the work now dispersed across a variety of private and public collections—minus any iteration that might have been destroyed or accidentally discarded by someone thinking it was an artful bit of trash, which it kind of is. (This has happened with Beuys’s work before.)

Beuys made the fried fish multiples following a performance at artist Daniel Spoerri’s aptly named Eat Art Galerie, an experimental space situated in Düsseldorf above Restaurant Spoerri, which the artist also operated. The gallery had opened on September 18, 1970, with an exhibition of Spoerri’s own Brotteigobjekte, a series of everyday objects—such as rotary telephones, typewriters, and shoes—that had been used as vessels for baking bread, with the resulting works looking quite grotesque and alien, as if they had been invaded by out-of-control, overproofed dough.

A little over a month later, at the end of October, Spoerri hosted Beuys at the gallery. While there isn’t as much documentation of Beuys’s performance as I’d like, Spoerri—who himself deserves a much longer discussion that I promise to provide in a future Weekly Special!—described Beuys’s performance (and its gestation) at length in a matter-of-fact interview in December 2015, which I’ve translated here from the original German. (Please note: towards the end of the interview, he uses an offensive racial term.)

Spoerri recalled:

[Beuys] had always cooked, not his wife. And he cooked like a farmer: he didn’t peel potatoes with a peeler, but instead peeled thick sections with a knife because you could give them to the pigs. […] I ate once at Beuys’s place—there was herring, I believe—and he said, “By the way, I always eat the bones, there’s calcium. They’re so thin, you can eat them with the flesh.” That stuck in my memory and in his too, evidently.

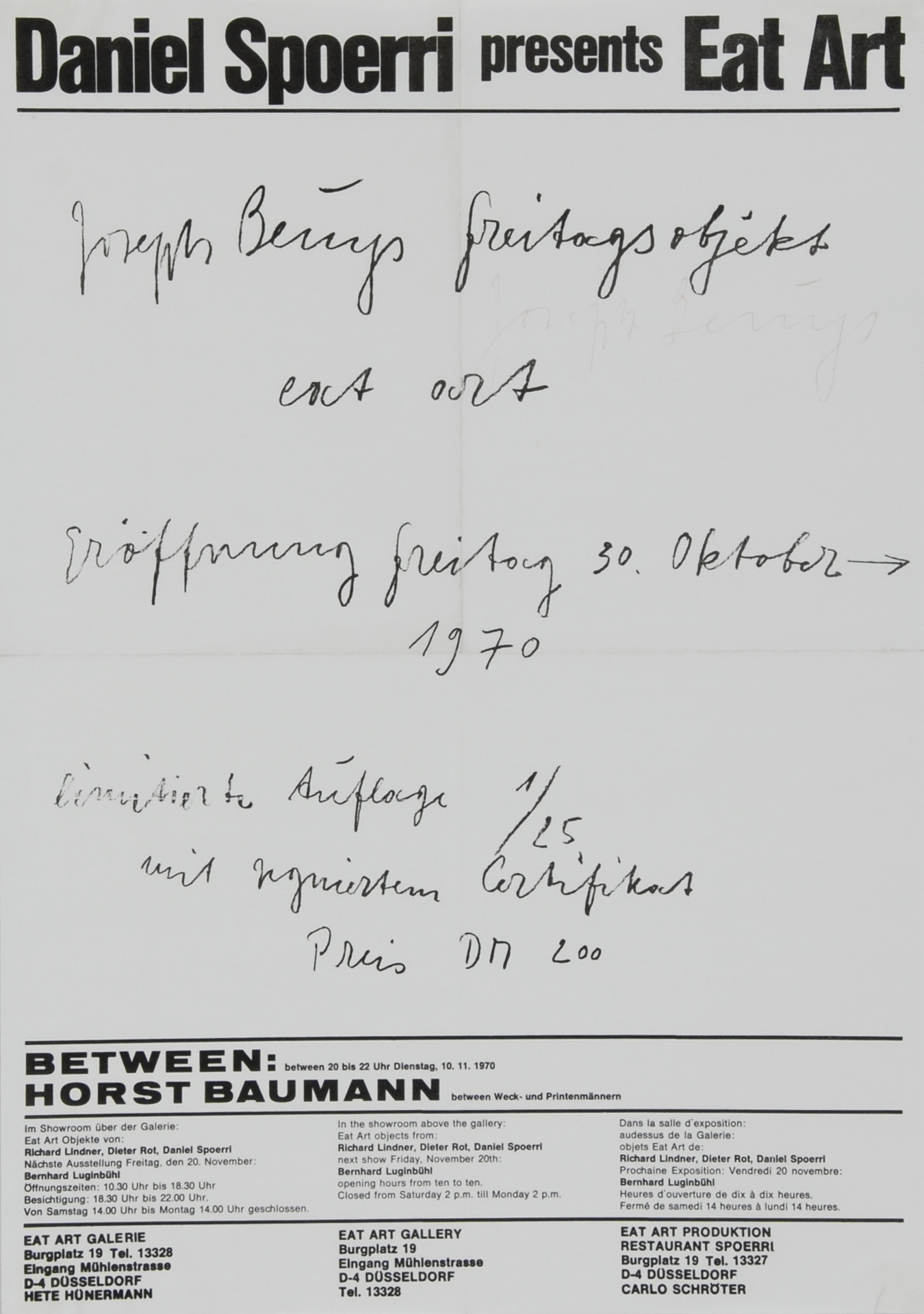

I visited him at some point at the [Düsseldorf Art] Academy to ask if he would make something for the Eat Art Galerie. With a pencil, he wrote directly on the poster for the exhibition which I had brought: “1st Class Herring Bones.” [Editor’s note: The poster doesn’t actually say that, as you can see below.] The gallery cost me 5000 Deutsche Marks (DM) per month, so I had to make that much in order to keep the gallery going. Beuys said, “We’ll make 25 objects at 200 DM. Then you’ll have your 5000.” As people learned that Beuys was making an object for 200 DM [roughly $380 in 2021 money], everyone wanted one. There were so many people interested that we had to let a lottery decide.

On the day of the opening, I picked Beuys up from his house at 9am. In a box he had the herring bones and greaseproof paper neatly laid on top of one another so that nothing would be damaged. He spent all day in the gallery hanging the bones from threads with great care. Twenty-five fishbones from 25 little nails. He refused to come down to the restaurant to eat because he wanted to concentrate. So we brought up a steak for him. It was wonderful, how quietly and diligently he worked.

The opening was at 6 or 7. Beuys took a bit of charcoal out of his bag, stomped it on the floor, and rubbed it on his face. Then he played two cassette tapes, which repeated just two words: “Ja, ja, ja, ja, ja” and “nee, nee, nee, nee, nee.” [Yes and no.] Because he played both tapes on the same reel, one heard: “ja, nee, nee, nee, ja, ja, nee, nee, nee, ja, nee, nee, nee.” He had the tape recorder around his neck. Leaning on a thick staff, he stood there with his black face. “Friday-Object,” he called it. In the story Robinson [Crusoe], the “negro” was also called Friday. “Did you mean that Friday,” I asked him, and he asked back, “Daniel, have you picked up on something?”

He had sewn a dried herring onto his jeans. And it had a stamp that said “Gleichstrom” [direct current]. The whole thing was a complicated story. At the end he wrote on numbered pieces of paper: “1st Class Herringbone.” That was the certificate. There were maybe 40 people who wanted to reserve an object before the opening. Eight of them changed their minds, saying, "I’m not paying 200 Marks for this shit." I then bought these eight fishbones for myself. And the last one I gave two or three years ago to a girl for whom Beuys was God. In any case, it was a nice and well-rounded thing.

Wow.

I hadn’t come across this interview until last week, and “complicated story” seems like a massive understatement. There’s a lot to unpack here, as the academics say, and I won’t even try to do justice to all of it.

First, I had always understood the title “Friday Object” to have something to do with the tradition of eating fish on Fridays during Lent, which makes sense given a range of other Catholic references in Beuys’s oeuvre. But Spoerri’s description of the performance—which I had previously known only through a handful of photographs published in a later artist’s book (shown above)—renders that simple explanation pretty inadequate. What of the blackface, if indeed that’s what it is? What of the possible reference to Robinson Crusoe? I wouldn’t put it past Beuys to nod to an English adventure novel, and there is indeed a lot of fishing in that book, if I recall correctly… but I’m not sure I can (or should) weave the Crusoe story, Lenten fish traditions, and an audio track of “ja ja ja nee nee nee” (which I’ve heard Germans fondly refer to as grandparent speak) into a coherent interpretation.

The grandparent speak does point to another possible context for the work, though, and one I find especially compelling: the aesthetics of want or poverty, which recur in Beuys’s work over and over, calling up the dire circumstances of wartime and its aftermath, when one very well might have eaten the bones along with the flesh, not wanting to waste the slightest bit of a solid meal. That kind of resourcefulness and frugality, born of necessity, still resonates.

For Further Eating

I started writing this week’s newsletter while in Los Angeles, which meant no kitchen to cook in and therefore limited ability to develop or test my own fried fish recipe. (I mean, I could’ve hijacked my friend’s stove, but who wants an apartment filled with fish-scented oil? Not exactly the “thank you so much for hosting me” that I usually go for.) Naturally this meant I had to seek my fried fish elsewhere, and where else but the beach? When I lived in LA previously, I seldom went to the beach, but when I did go, I always made an obligatory stop at Malibu Seafood, a tiny establishment perched right on the PCH, with umbrella-topped tables and a vast array of fresh seafood prepared however you want it.

This time I waited until I had found a place to live—my main mission in the city besides installing my Beuys show—so I could drive to Malibu in a spirit of calm and celebration, shedding some of the frantic energy of apartment-hunting that had consumed the days previous. After standing in an appropriately long line, I ordered a cup of New England clam chowder and a plate of fried cod and fries, which I doused in malt vinegar and hot sauce and ate slowly while people-watching and trying my best to avoid a wicked sunburn.

Trips to Malibu Seafood feel like a pilgrimage, but one that I make gladly, despite the horrific traffic, because there’s nothing like inhaling fresh fish as it mingles with the salty smell of the ocean.

Part II

Back in landlocked Oberlin, Ohio, I realized my desire for fried fish hadn’t been totally sated. The Lenten fish fry season that engulfs nearby Cleveland every winter ended months ago, but my favorite local fish dish—a beer-battered Lake Erie walleye—is a menu staple at the nicest restaurant in town, 1833 (named for the year Oberlin College was established), where I’ve had dozens of boozy post-lecture dinners. I had wanted to order the walleye a few times at the height of the pandemic, when the restaurant was take-out only, but I always wound up settling for steak or short ribs instead, fearing that a humid takeout box would ruin my crispy fish and therefore also my mood.

Now that indoor dining is back on, I took myself to lunch for my long-awaited walleye.

With Midwest proportions (this thing is bigger than my head), a shatteringly crisp cloak of skin, and a side of garlicky fries, it was even better than I remembered.

Great post, Andrea! Not only did it refresh (and revise) my Beuys knowledge, but it resonated deeply with my weekly fish adventure, courtesy of Poiscaille, a fishy version of the produce box.