Digging in the (Orange) Crates

Ben Sakoguchi's long-running series of paintings based on vintage orange crate labels, plus an orange-based recipe from a new memoir 🍊

Welcome to the latest issue of Weekly Special, a food-art newsletter by Andrea Gyorody.

Hello and happy February!

It’s full-on citrus season, so it feels like an appropriate time to celebrate the work of Ben Sakoguchi, who has been making paintings based on the format and motif of the vintage orange crate label for nearly 50 years. I first encountered Sakoguchi’s paintings in 2022, in Bel Ami’s booth at Frieze LA. I was charmed by some of the most recent additions to this long-running series, including several that referenced Covid with tongue-in-cheek commentary on cruise ships (“Cruisin’ with Covid” Brand Oranges, from Corona del Mar, CA) and a thoughtful homage to Dr. Li Wenliang, the Chinese physician who first alerted the world of the virus’s severity (“Dr. Whistleblower” Brand Oranges, from Death Valley, CA).

After that, it felt like I was seeing Sakoguchi’s paintings everywhere, coming to a head last fall, when I saw two of the orange crate paintings in Hilton Als’ gorgeous exhibition-as-portrait Joan Didion: What She Means, offering texture for Didion’s childhood years in the Golden State. Just days later, I read that Sakoguchi’s kaleidoscopic painting Comparative Religion 101 had been accepted then rejected from the Orange County Museum of Art’s 2022 California Biennial, which I had visited that week, none the wiser. The work had been dismissed, ostensibly, because one of its 15 panels includes a swastika, called manji in Japanese, painted with specific reference to Buddhism (where the symbol has a positive meaning, though Sakoguchi complicates that reading by aligning it with Japanese nationalism). The rejection came despite Sakoguchi’s thoughtful answers to a lengthy questionnaire the museum had sent him, essentially asking him to defend the painting and do the curatorial work of contextualizing it.

This act of censorship (conducted in private and then made public) put Sakoguchi’s work in the spotlight and inspired me to take a closer look at the orange crate paintings for Weekly Special. I’m very grateful to the artist’s wife, Jan Sakoguchi, and his studio manager, Jackie Tarquinio, for their prompt help answering my questions and providing all of the fabulous images you’ll see below.

Let’s dig in!

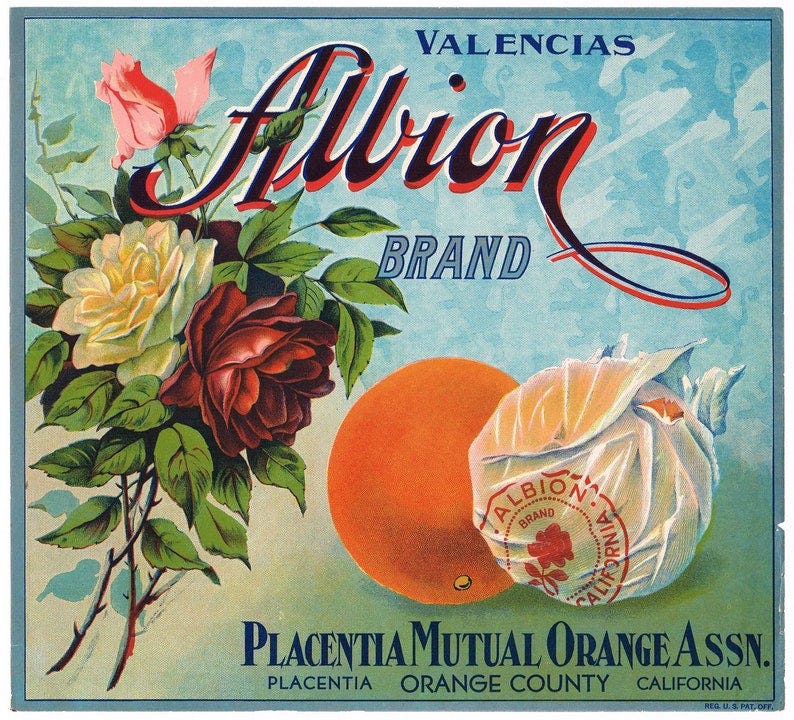

Ben Sakoguchi’s Orange Crate Paintings

From the 1880s until World War II, wooden crates of oranges grown in California were shipped out emblazoned with 10 x 11-inch full-color lithographic labels. A quick Google search for “orange crate labels” will turn up dozens of examples, many of them stunningly beautiful, selling not just oranges but the dream of California, verdant and blooming in the winter months of citrus harvesting, when the rest of the country is still in deep freeze. Many are also playful, with imagery that matches brand names such as Orbit, Wonderland, Shamrock, Miracle, and Eat-One.

Naturally all good and beautiful things come to an end, and after an eventual decline in wooden crate manufacturing, they were replaced by cardboard boxes printed with (comparatively boring) logos and brand information, making the once-ubiquitous labels unnecessary.

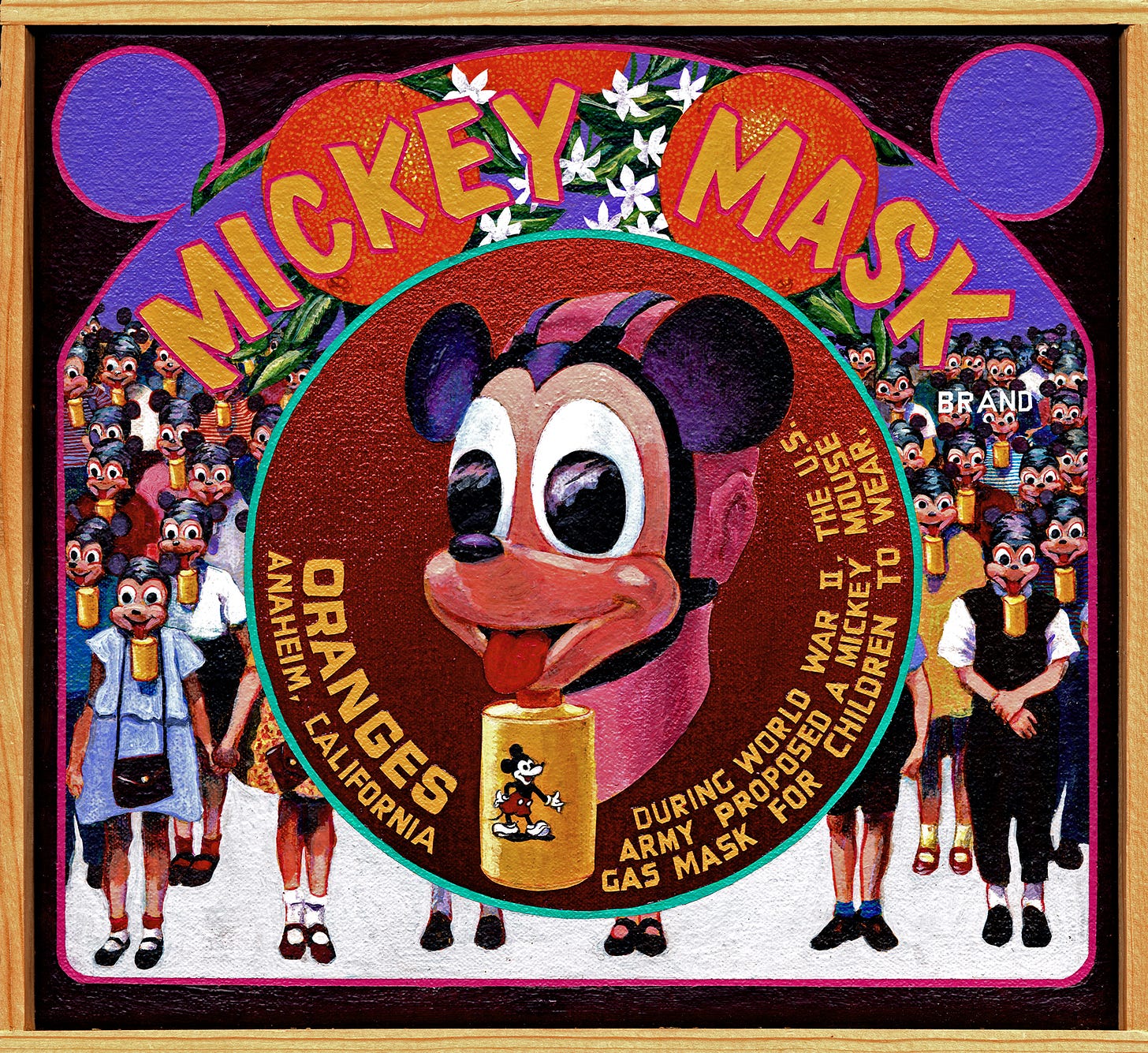

Several decades after orange producers retired their crate labels, painter Ben Sakoguchi started what has become a long-running series of paintings based on the format and conceit of the orange label, with a dizzyingly broad range of subjects drawn from sports, pop culture, contemporary politics, and historical events as divergent as the dropping of the atomic bomb and the wedding of Charles and Diana (one of a number of works commemorating doomed celebrity marriages).

Sakoguchi hadn’t always been eager to execute biting social and political commentary. As he wrote recently in response to a questionnaire about the meaning of his paintings, “In college, sixty-five years ago, I was taught that ‘fine art’ should NOT be political. It took me 10 years to unlearn this highly political concept, and another five to fully embrace using political subject matter in my work.”

Sakoguchi’s interest in war and violence, themes that recur across the orange crate paintings, stems in part from his own experience growing up in a Japanese internment camp in Poston, Arizona, where his family lived from 1942–45. Numerous of his paintings critique anti-Asian policies, including Yellow Peril, from 1974, and the atomic bomb painting above, made a year later. They also highlight the trauma of war, particularly for children, as in the horrifying Mickey Mask painting below.

Sakoguchi’s paintings are truly a mix of heavy and buoyant; just when it looks like he’s focused on something light, darkness enters back in. Among his many paintings spoofing modern art, for example, he swings from Bank on Frank Brand, making fun of Minimalism’s co-optation as corporate lobby art, to The Floor Belongs to Carl Andre, which draws a connection between Andre’s game-changing floor-bound sculptures and the final position of the body of Andre’s wife, artist Ana Mendieta, whom many believe was pushed from a window by Andre himself. (He was tried and acquitted for her murder, as detailed in a recent podcast.) As disturbing as the content is, I couldn’t help but laugh at the locale Sakoguchi had assigned to the brand: Carlsbad, California.

In this kaleidoscope of culture, there are truly joyful moments and truly heinous ones, examples of human excellence and perhaps more of human hypocrisy, hatefulness, and failure. Here are a few more of my favorites, which include tributes to Muhammad Ali (one of Sakoguchi’s most beautiful paintings, IMO) and baseballers Josh Gibson and Babe Ruth (with a subtle critique of the racialized terms by which athletes are often characterized), alongside a send-up of Rei Kawakubo’s maligned 1995 menswear collection (pulled from production because the garments resembled concentration camp uniforms) and a memorial to two reproductive health center employees shot to death by a “pro-life” activist in 1994.

As I’ve spent more time looking at Sakoguchi’s work, I’ve realized that the central conceit of these paintings — melding references from current and historical events with the bygone marketing language of California-grown oranges — allows the artist to offer stinging commentary without being overly didactic or humorless. Individually, these works strike me as anti-history painting, rejecting the monumental in favor of the commercial, ornamental, and ephemeral. But when we consider the massive scope of this entire — still ongoing! — series, it morphs into a deeply compelling collage of the past 80 years. It’s history painting in fragments, apropos of our post(post)modern age, where anything can be spectacle and the orders of magnitude that (ought to) separate royal weddings from incidents of mass violence have been flattened, ultimately rendered part of the same brutal news cycle that apportions coverage based on projected revenue.

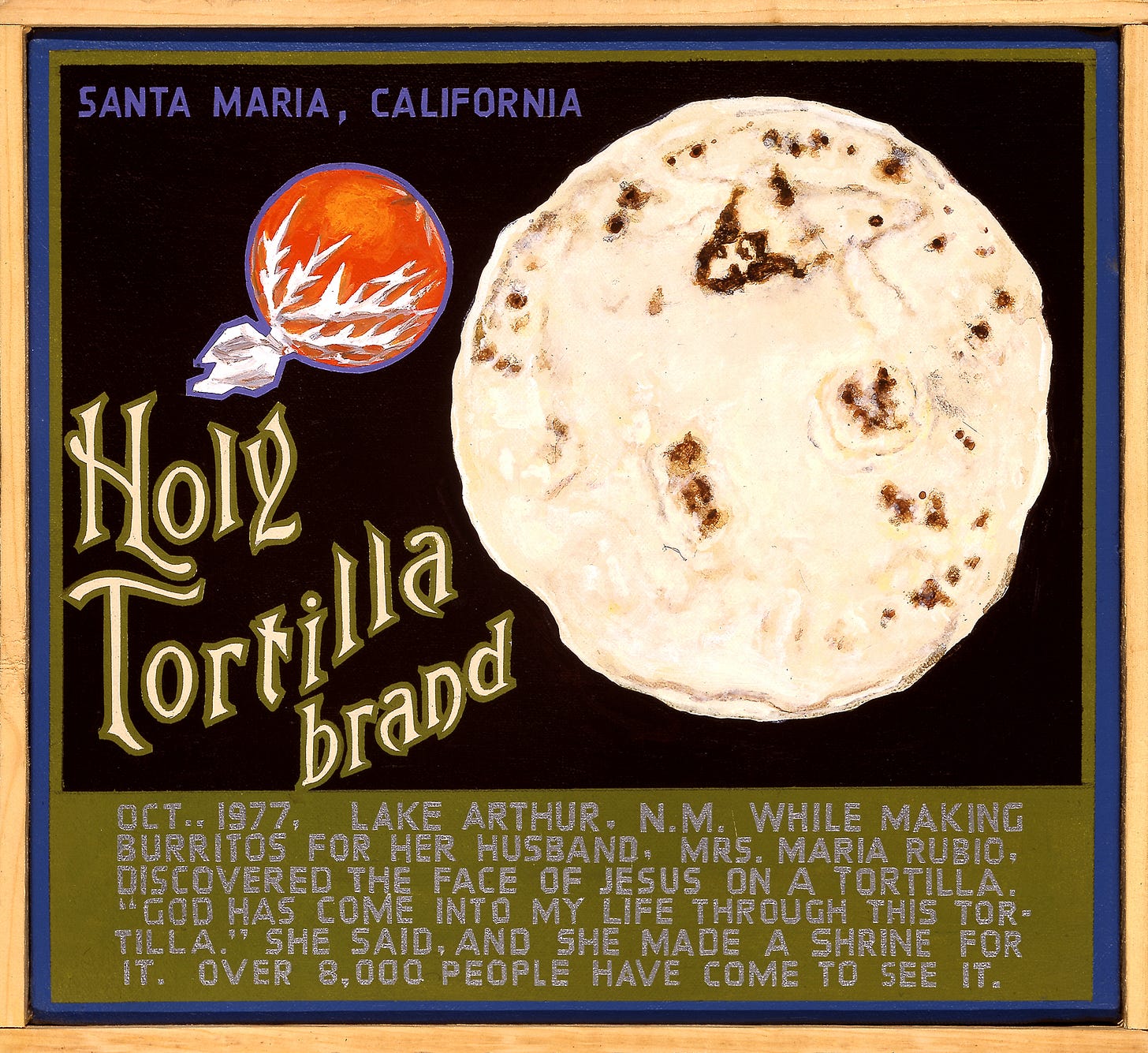

There’s perhaps a more optimistic way of thinking about this notion of history painting in fragments, though — one that I discovered, incidentally, in this painting about a tortilla purported to feature the face of Jesus.

Sure, we could see Holy Tortilla Brand as mocking religious zealots. But we could also see the popularity of this tortilla as a symptom of the desire to find meaning — signs of the divine — in the quotidian, and to seek connection with a higher power as an escape from this messy, confusing, and cruel world. The more humble and unassuming the vehicle, the better.

One Last Bite

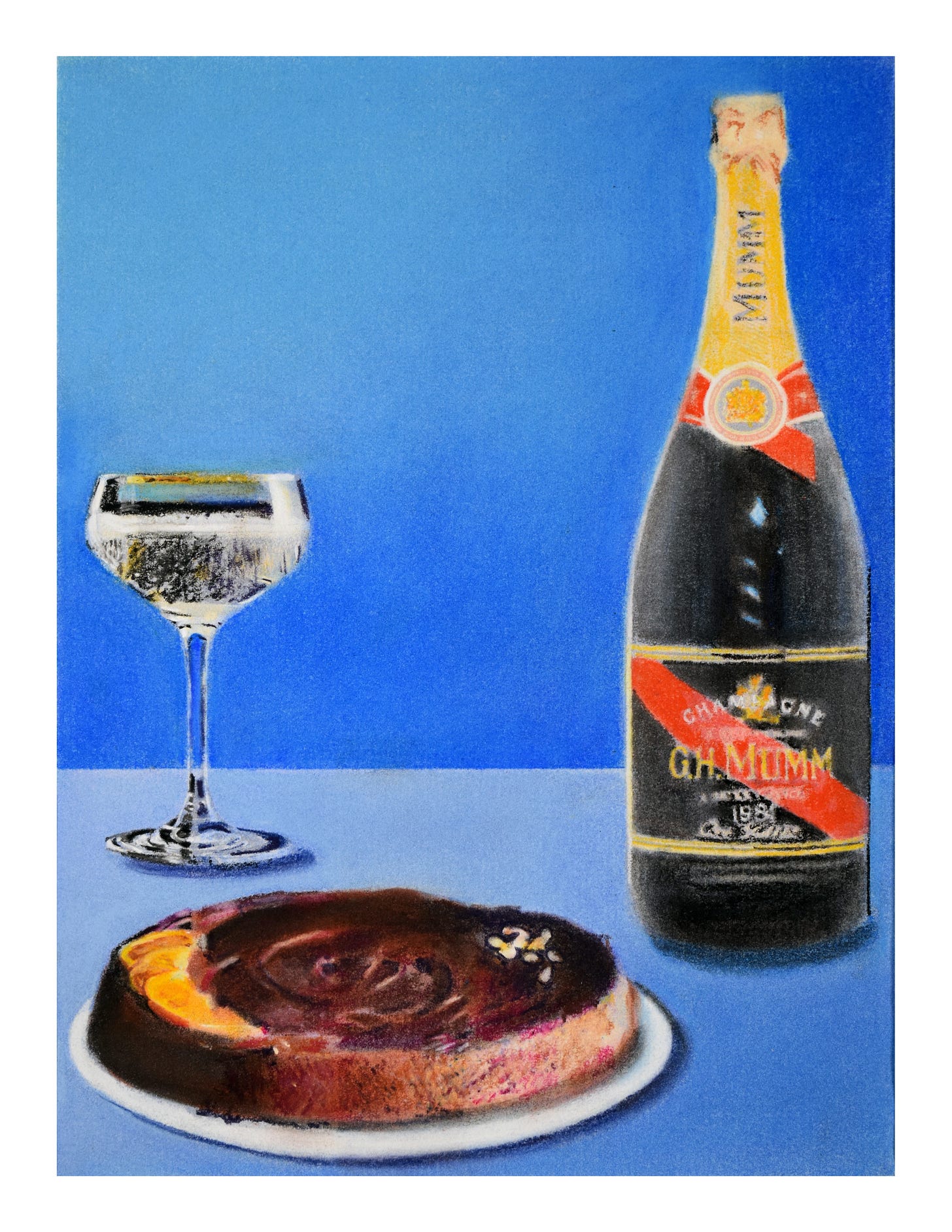

Naturally, Ben Sakoguchi’s work had me thinking about orange recipes, which happen to be peppered liberally throughout a brand new illustrated memoir scheduled to be released this March. Written by art historian Mallory M. O’Connor with her artist-husband John, The Kitchen and the Studio: A Memoir of Food and Art chronicles their lives through the meals they’ve eaten since their first date in spring 1962, after becoming fast friends in Wayne Thiebaud’s drawing class at the University of California, Davis. (They just celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary last month.) Mallory has kept a diary of every meal they’ve enjoyed, from that first date (John made sushi and Crab Louie) to a brunch they served for one of John’s former students (featuring paella and caramel sea salt ice cream with Kahlua) just a few weeks before the pandemic lockdown began.

With their permission, I’m sharing their recipe (and John’s painting) for Chocolate, Orange, and Almond Torte, which was served for John’s 48th birthday, on January 23, 1988, at their home in Rancho Micanopy, just south of Gainesville, Florida. The torte capped off a feast of cheese biscuits, beef filet with red wine sauce and mushrooms, potatoes with rosemary and garlic, green salad with chèvre, and French bread, served with a 1980 Beaulieu George de la Tour Private Reserve Cabernet — but it could just as well be the sweet ending to your next romantic dinner.

Chocolate, Orange, and Almond Torte

Serves 12

For the torte:

1 ½ cups blanched almonds, toasted

8 ounces bittersweet chocolate, chopped (Lindt Swiss is among the best. Ghirardelli also makes a lovely chocolate baking bar that is 100% cacao unsweetened chocolate, although some folks will tell you that Ferrero Rocher is the all-time winner. Take your pick!)

½ cup unsweetened cocoa powder

6 large eggs, separated

1 cup sugar

½ cup orange juice

1 tablespoon grated orange zest

14 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

½ tsp sea salt

For the topping:

1 cup heavy cream

½ cup sugar

3 tablespoons orange marmalade

Method:

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees and coat a 10-inch springform pan with cooking spray.

In a food processor, pulse the almonds and the chocolate until finely ground. Add the cocoa powder and pulse to combine.

In a medium bowl, whisk together the egg yolks, sugar, orange juice, and zest until thick and creamy. Beat in the chocolate-almond mixture and the melted butter.

In another bowl, beat the egg whites and salt until stiff peaks form. Gently fold the egg whites into the chocolate mixture and pour it into the prepared pan.

Bake until the cake pulls away from the pan edge, about 50 minutes. Let cool completely on a rack before serving.

To serve, run a knife around the edge of the pan and invert the cake on a serving platter.

Whip the cream with the sugar until soft peaks form. Beat in the orange marmalade.

Cut the cake into wedges and top with the orange whipped cream. Garnish with a pinch of orange zest if you like.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, take a second to “like” it — that helps me find new readers. If you want food-art content even more often, follow Weekly Special on Instagram, where I share many more tidbits (on Stories) than I write about in the newsletter.

Go enjoy some art and food IRL, and see you again soon!