Deconstructing [Salmon]

Guest writer Aaron Gonsher delves into the color story behind Cooking Sections' book and exhibition project "Salmon: A Red Herring" 🐟

Welcome to the latest issue of Weekly Special, a food-art newsletter by Andrea Gyorody.

Happy May! The sun in LA is finally shining (most days, anyway) and the hills are alive with so. many. flowers. We haven’t driven out to see any of the much-publicized superbloom sites because we’ve been getting our flower fix much closer to home, driving through our neighborhood (where one house has been practically obliterated by bougainvillea) and on the way to work in Malibu — a commute that is marked by ocean to my left and cliffs studded with chartreuse, aureolin, and fuchsia to my right.

But there’s no such thing as beauty without some price being paid,1 even beyond the devastating rains that ushered in all of this growth. Sure enough, that eye-tickling acid yellow I see on my drive is Scotch broom, an invasive species that originated in Europe and North Africa. It’s now found up and down the West Coast, where it acidifies the soil, displaces native plant species and, because of the rate at which it burns, contributes to the speed and intensity of forest fires. Sigh.

This issue of Weekly Special, written by guest contributor Aaron Gonsher, tells a story about how color — and our socialized notions of beauty and health — not only mask environmental harm but very directly contribute to it. The subject of Aaron’s essay is a project called Salmon: A Red Herring, by UK-based artist duo Cooking Sections, which articulates the crucial role aesthetics plays in our consumption habits. Fair warning: if you haven’t yet been put off farmed salmon by extensive reporting about unsustainable practices and rampant sea lice, you might be renouncing the artificially pink stuff by the end of this issue.

Let’s… dig in?

Deconstructing [Salmon]

by Aaron Gonsher

After finishing Salmon: A Red Herring, I made an ill-advised decision to visit the fishmonger at my local market. The person behind the counter didn't understand why I wanted to take photos, but my interest was aesthetic, not culinary. I'd spent the last few days reading the depressing, entertaining book by the Cooking Sections artist duo Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe, and the filets on display had, at least temporarily, ceased to appear as anything appetizing. The glistening fish on ice looked like what I'd been retrained to see: precision-engineered Pantone swatches. They were in ranges I previously thought I had the vocabulary to describe — pink, orangish, "salmon" — but which now communicated quantifiable color above all else: 1555U, 1565U, 487U, 1635U, 1575U, 157U, 486U, 1645U, 1665U, 485U, 2347U.

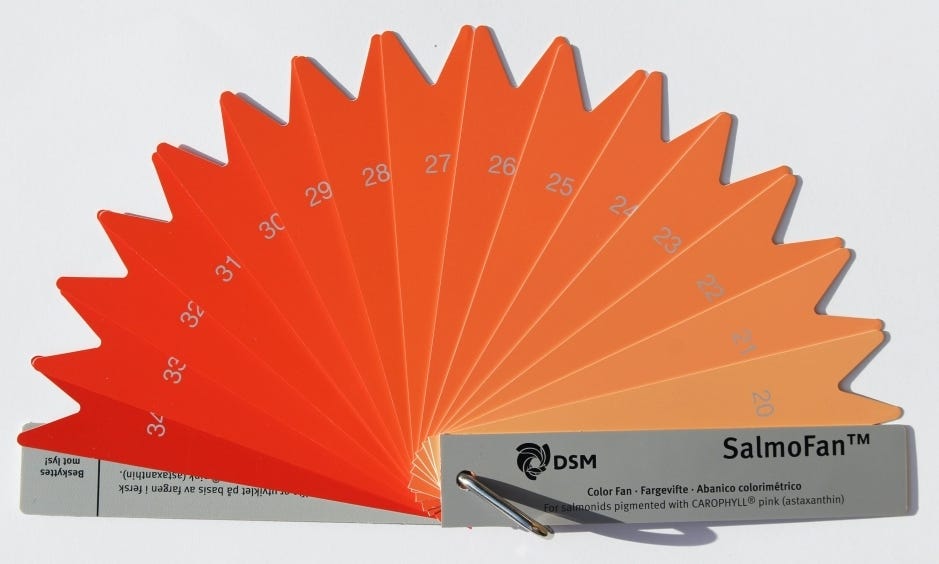

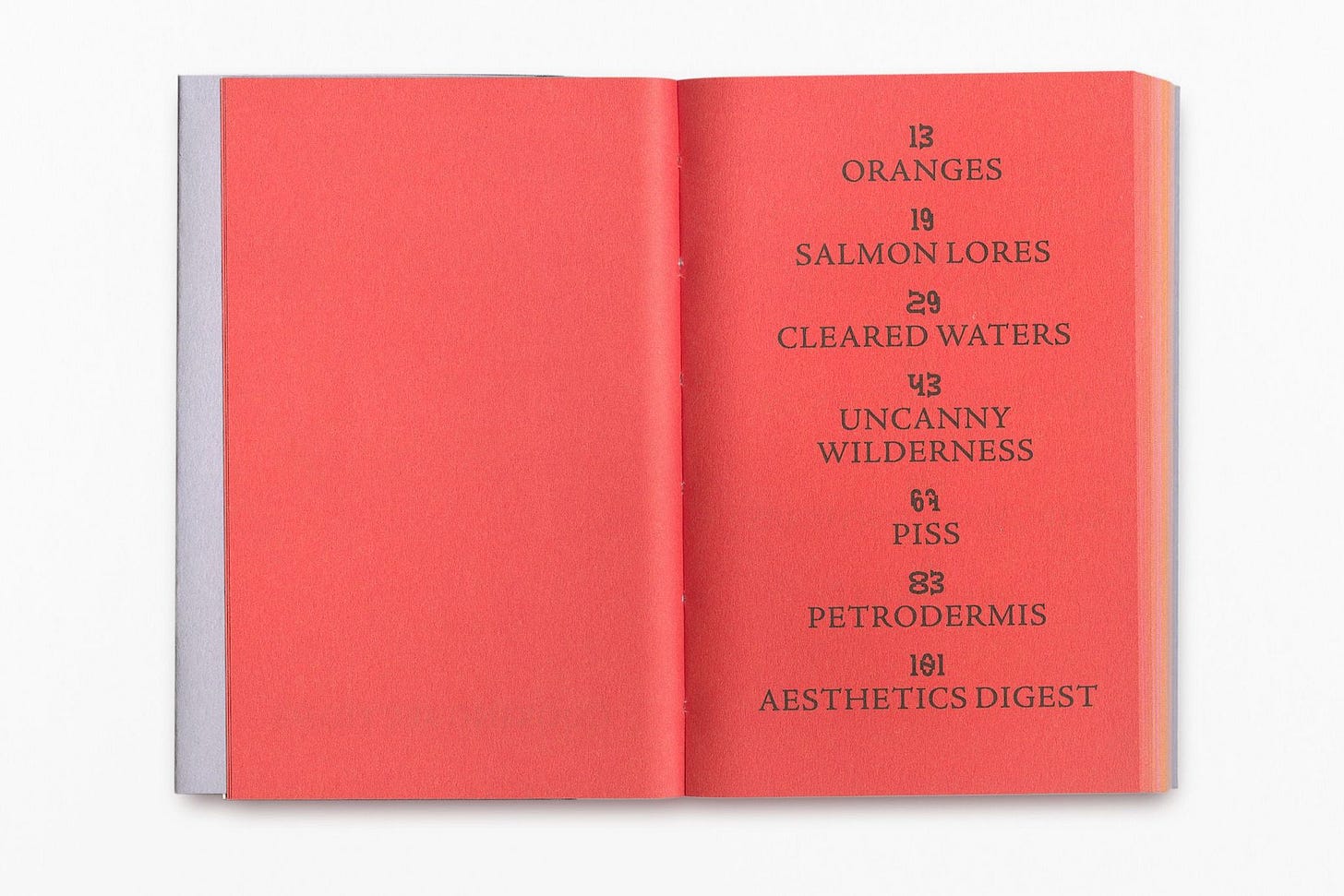

Those are the 11 Pantone numbers that comprise what Cooking Sections calls “[salmon]," according to the SalmoFan™, a classification and reference system invented by Hoffman-La Roche to guide the amount of synthetic color in the feed of farmed salmon required to achieve a specific hue. The average employee of an aquaculture farm has tools at their disposal to match any painter’s palette, though these hues are based on economics and not expression. Darker "[salmon]" is generally more expensive and has more astaxanthin in its feed, which dyes the flesh. Lighter farmed salmon has less astaxanthin, and is perceived to be cheaper and lower quality, though there are varied geographic preferences. Wild salmon get their color through a diet of crustaceans rich in natural astaxanthin, such as shrimp and krill, and absorb fat-soluble pigments called carotenoids. But farmed salmon isn't authentically pink – it's gray. According to Cooking Sections, these fish are not "salmon" in the natural sense we assume, but "[salmon]," a far more slippery and industrialized identifier.

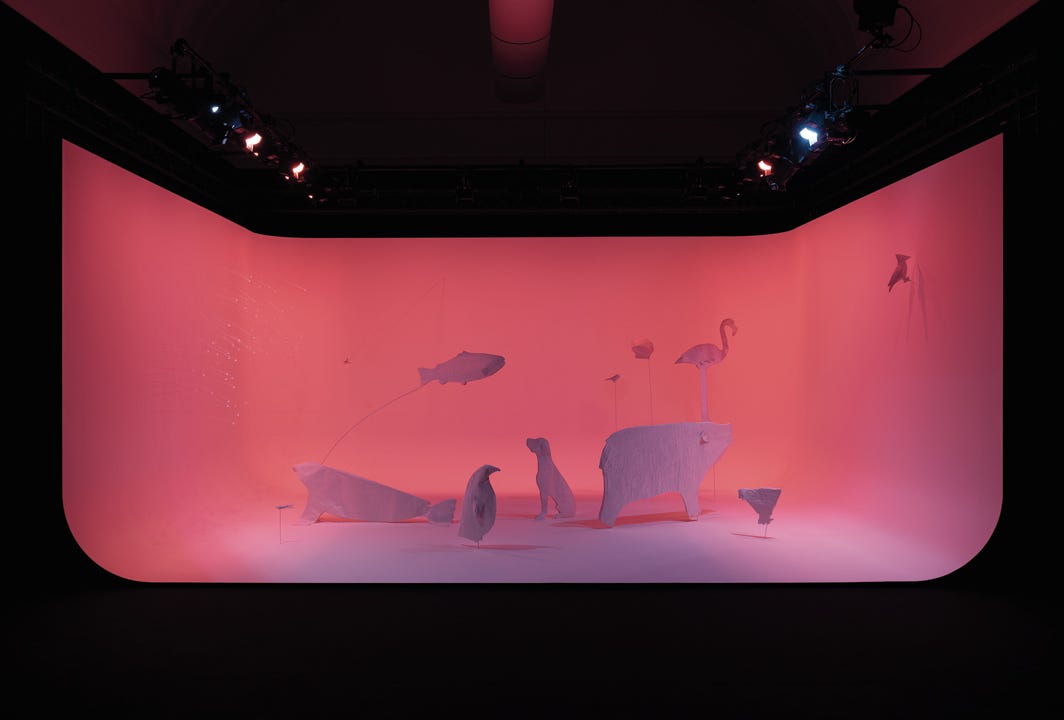

Salmon: A Red Herring is both a book, published in 2020 by isolarii, and an installation of the same name at Tate Britain, on view from November 2020 through August 2021. In the lead up to the project, the London-based Pascual and Schwabe, who describe themselves as “spatial practitioners,” spent time in deep research on the destructive culture of [salmon] farming on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. The site serves as a harvest and transport hub for worldwide trade of the fish and has a population ratio of approximately 1,600 fish for every person. Their collaboration with the Tate resulted in more than just an exhibition: it led to all of the museum’s restaurants and cafes removing farmed salmon from their menus in favor of "a CLIMAVORE dish – in perpetuity."2

Salmon is part of Cooking Sections’ ongoing CLIMAVORE project, which starts from the question, "how does what we eat as humans change climates?" Initiated in 2015, CLIMAVORE has developed additional works including Mussel Beach, which "navigate[d] the past, present, and future of Muscle Beach, California, by looking at mussels”; Wallowland, which was commissioned for the 17th Istanbul Art Biennial and featured a pudding shop, field recordings, and a celebration centering water buffalo and their herders; and To Those Who Nourish, an ongoing project to rehabilitate Lake Erie, commissioned for the 2nd FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art in 2022 and overseen by Cleveland arts organization SPACES.

“Climavore” is an apt term for the current moment, as eaters grapple with dietary choices within a destructive global food system. It follows in the footsteps of “climatarian,” defined as “a person who chooses what to eat according to what is least harmful to the environment,” which entered the Cambridge Dictionary in 2016. These are two of many approaches that take sustainability as a starting point; see also: locavore, reducetarian, and regenivore, the last of which differs in scope from “climatarian,” at least according to the New York Times food trend predictions for 2023, in that "it’s no longer about eating sustainably, which implies a state of preserving what is. A new generation wants food from companies that are actively healing the planet through carbon-reducing agriculture, more rigorous animal welfare policies and equitable treatment of the people who grow and process food."

Other food writers and outlets are also on the beat. That includes the new media platform Whetstone, which routinely emphasizes environmental impact in its reporting across print and podcasting, and figures as mainstream as Mark Bittman, who publishes instructive guides to shopping for sustainable fish. (Civil Eats is also consistently excellent on these subjects, reporting widely on efforts farmers are making to address the effects of climate change.) This awareness of what we eat and how it gets to our plates has also been platformed at high-profile art institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which staged Food: Bigger than the Plate in 2019, bringing “together the politics and pleasure of food to ask how the collective choices we make can lead to a more sustainable, just and delicious food future."3

In the case of Salmon: A Red Herring, politics are omnipresent, pushing pleasure entirely off the menu. The real focus is perception: why it matters and how it has been denaturalized, enabling us to participate in aesthetic manipulation — paradoxically — as blissfully unaware, though still visually discerning, consumers. Cooking Sections pinpoints this reality in one of the book's key theses: "Colour is the species we consume."

Salmon: A Red Herring is compact and convincing, with deep historical research alongside poetic analysis. As a tool of activist art, it's even more successful: I'm never going to be able to eat a piece of salmon without thinking about its path to my plate and what it took to get there looking the way it does. These individual starting points are essential for any societal reckoning with industrial food systems and their damages. It's intervention on a personal scale, indictment on a global one.

The book’s pages are colored according to the Pantone hues that make up the Hoffman-La Roche SalmoFan™ palette, while each of the book’s 12 chapters (save for first and last) is prefaced by quotes that reference dictionary and encyclopedia definitions of "salmon." The inconsistency among the definitions indicates how unreliable a concept [salmon] is, but the best and most accurate is the artists’ own: [salmon] is “a colour bound to the body, a body bound to its own name.”

About those brackets: [salmon] is Cooking Sections' own shorthand, highlighting both the artificiality of contemporary foodstuffs and our complicity in erasing natural environmental realities through our rapacious visual preferences and biases. The punctuation underscores the artists’ overall argument, and it’s not just salmon that gets this treatment — there are digressions on [sparrows], [pigs], [cows], and [humans]. The brackets become a constant stylistic reminder that, like the modified [salmon] Cooking Sections decries, things are not what they seem, even if we persist in calling them by the same names we always have.

To understand how we got here, Cooking Sections traces the origins of manipulated color in food production, which they attribute to a desire for control in a world of uncertainty. They assert that color charts guiding this drive have a urological basis, at least in Europe, where diseases were once diagnosed by the shade of one’s urine. Our socialization into color as an indicator of health then spread to our relationship with foodstuffs, leading growers to go to great lengths to ensure a consistent look for their products. At the turn of the 20th century, oranges ripening too fast in the humid Florida climate, for example, were ready to be eaten while green, but growers felt obligated to synthetically dye them orange, "coated to match consumer expectations."

Cooking Sections further discusses the origins of dyes in feed through the DSM’s YolkFan™ grading system, and synthetic dyes like Carophyll Yellow, used to mimic a nutrient-rich yolk color from grasses and flowers that farmed chicken don't ever get to eat.4 They also point to the onetime enforced dyeing of margarine in the US as a political concession to a powerful dairy lobby. This obsession with color, and the role it plays in our capitalist, industrialized society, is summarized succinctly in their notion of “the colour economy.”

Salmon: A Red Herring is an unsettling read, packed with references and provocations. In the hands of Cooking Sections, color is memory, asset, weapon, tool, mode of distinction and discrimination, and the defining factor of perception, whether the object of our gaze is in a frame or lies behind the fish counter.

To be sure, we’re all ensnared by the color economy. I myself am a willing participant: the socks I’m wearing as I type were marketed as the Pantone color code of Prince’s purple; that’s why I bought them. In the end, we’re not so different from salmon: they eat the lures they find attractive, and we do the same when we shop with our eyes. The beauty of a wild salmon’s true colors, acquired through diet, health, and mating, is the product of transformation only found in nature. But wild salmon is beautifully inconsistent and unpredictable. It's a contingency that the market, and we as socially conditioned consumers, won’t tolerate — even if doing so would help avoid spiraling environmental destruction.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, take a second to “like” it — that helps me find new readers. If you want food-art content even more often, follow Weekly Special on Instagram, where I share many more tidbits (on Stories) than I write about in the newsletter.

Go enjoy some art and food IRL, and see you again soon!

For more on beauty’s dark side, see Katy Kelleher’s recent book The Ugly History of Beautiful Things. Apropos of Cooking Sections’ work, there’s a chapter dedicated to the mollusk!

According to the Tate website, “Chefs [at Tate Eats] have created new dishes using sea-foraged ingredients, which has resulted in two new additions to Tate menus: Fermented whole grain barley and kelp broth with soda bread, and a roasted carrot, orzo and kale salad with sea lettuce and walnut pesto. Tate Eats has also worked with Cuillin Brewery on Skye, to create a new Seaweed IPA. Seaweed is a key component of the ongoing Cooking Sections menus and dialogue, as it cleans and oxygenates sea water. The kelp and sea lettuce used in the Tate menu comes from the Cornish Seaweed Company, supplier of organic handpicked edible seaweed from the west coast of Cornwall.”

Editor’s note: It would be utterly impossible to list all of the recent exhibitions and art-adjacent projects that engage the environmental ethics of food, but here are a few more to check out: Food in New York: Bigger Than the Plate (at the Museum of the City of New York, through September 2023); At the Table (Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena, 2022); Better Food Future (virtual, 2021–22); Food for the People: Eating and Activism in Greater Washington (Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C., 2021–22); and Food by Design: Sustaining the Future (Museum of Design Atlanta, 2017).

The DSM is a major player in the food and nutrition market, developing and distributing synthetic vitamins, nutrients, flavors, and feeds worldwide. The acronym DSM originally stood for Dutch State Mines, but the company has long been known simply as DSM, having diversified beyond mining early in its history.

😮

I definitely saw shades of yellow yolks in Ukraine that I could only dream of finding in the states. I wonder if this stuff they feed the salmon is the same stuff they feed to flamingos to increase their pinkness? 🤔