White Asparagus

Édouard Manet's "Bunch of Asparagus," 1880

Welcome to the second issue of Weekly Special, a food-art newsletter by Andrea Gyorody.

It’s Spargelzeit!!! (If you know, you know. If you don’t, read on.)

But first: thanks to all who read, enjoyed, and shared the first issue, and welcome to all newcomers! I’m excited to have you aboard and would be delighted to hear from you; just hit reply on this email to contact me directly.

If you’ve landed here but you’re not yet subscribed, you can do that right now:

Before we get to our artwork of the week, a few things to share:

Many of you have seen the guide to art cookbooks I wrote for the lovely Paula Forbes at Stained Page News (which is entirely dedicated to all things cookbook), but in case you haven’t, you can check it out here.

I’m now regularly posting food-art news on Weekly Special’s IG Stories. I’ve posted links to print benefit sales, new museum acquisitions, recently published books and articles, and more. Follow along here, and send your friends over, too! (And if you have any hot tips, send ‘em my way by DM or email.)

Now let’s dig in!

This Week’s Special

Édouard Manet

Bunch of Asparagus, 1880

Oil on canvas

Collection of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum

After many false starts, summer has finally hit northeast Ohio! Among other glorious things, the warm weather has brought a bounty of fresh asparagus to my local farm stand, which has just started to offer bunches of white, green, pink, and purple.

The sight of white asparagus invariably sends me back to the two years I spent doing PhD research in Germany, where the season known as Spargelzeit sends people into a frenzy. (It’s not quite World Cup-level excitement, but it’s not far off, which is pretty remarkable for a vegetable.) My first spring in Cologne, I was bemused to witness produce sections everywhere overtaken, practically overnight, by shrines to the perennial plant. On top of that, it seemed nearly every restaurant across the city advertised Spargel specials—not necessarily any specific dish, mind you, but the mere availability of Spargel on the menu, reassuring potential diners that eating there could satisfy their daily fix.

In the midst of all that Spargel activity, I discovered that Cologne also happens to be home to art history’s greatest ode to white asparagus:

Édouard Manet’s Bunch of Asparagus, painted in 1880, lives at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, the somewhat stuffy counterpart to Cologne’s hip Museum Ludwig. The painting is small, about 18 by 21 inches, and dominated by a fat bundle of white asparagus with purple tips, bound with twine and cradled by a grass-green pile of leaves. Manet’s handling of paint is loose and impressionistic: in some places, brushstrokes serve to distinguish a spear or leaf from its neighbor; in others, individual strokes of oil paint are subsumed into an abstracted mess of color, as where the asparagus tips meet and dissolve into splotches of pink, purple, yellow, and white.

The angle of the asparagus—up and to the right—has always struck me as a bit funny, as if the whole bundle might take off in flight. In this regard, Manet’s painting bears a striking resemblance to a much earlier work by 17th-century Dutch artist Adriaen Coorte, whose projectile asparagus glows eerily against a moody black background.

The dynamism in Manet’s work also owes to the way his brushstrokes flit rightward across the surface of the canvas, giving the whole thing a sense of propulsive direction. Put that together with the fact that this is a painting of fleshy, turgid, incredibly phallic vegetables, and yeah: it’s suggestive. (French philosopher Georges Bataille, who was all about eroticism, cryptically called Manet’s painting “lively.”)

I’ll spare you the full-on psychoanalytic reading, but I will note that there’s a long history of asparagus being marketed as an aphrodisiac. There’s no scientific evidence that asparagus has any impact on libido or sexual performance, but that hasn’t stopped various cultures from promoting it, probably more because of its shape than any demonstrated effectiveness. According to this Nat Geo story, for example, bridegrooms in 19th-century France (where Manet made his home) were expected to eat loads of asparagus at their wedding feasts in preparation for consummation. (I’m guessing all they got out of it was stinky pee.)

Whether any of that entered into Manet’s thinking as he crafted this little portrait of asparagus, we can’t know, but it’s not far-fetched that the same guy who painted Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia in his younger days might have been thinking about sex when he painted a bundle of phallic vegetables.

Whatever the symbolic content of Bunch of Asparagus, the painting caught the eye of French-Jewish collector, critic, and art historian Charles Ephrussi, who bought it directly from Manet. The price of the painting was 800 francs, but Ephrussi sent 1000 (either in error or out of generosity), prompting Manet to dash off a pendant painting of a single spear, accompanied by a cheeky note that said: "There was one missing from your bunch."

Manet’s lone asparagus, with its engorged tip and ragged end, is full of pathos. It truly does look left behind, discarded at the edge of a greige sea of countertop while the rest of the bunch made it to the table. Asparagus remains abandoned, living at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (in excellent Manet company), while its “mother” painting resides 300 miles west in Cologne.

There might, in fact, be a more sinister history behind the paintings’ estrangement, one uncovered by none other than conceptual artist Hans Haacke. In the early 1970s, Haacke—who was born and raised in Cologne but had immigrated to the United States in the ’60s—was invited to submit a proposal for an exhibition called PROJEKT ’74, organized by the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum to celebrate its 150th anniversary. Haacke submitted a proposal for an installation titled Manet-PROJEKT ’74, in which Manet’s Bunch of Asparagus would be placed on an easel in the center of the gallery and surrounded with text panels detailing its provenance and, crucially, “the social and economic position of the persons who have owned the painting over the years”—including whether they had any known ties to the Third Reich.

Unsurprisingly, the committee charged with vetting proposals voted it down. Several artists withdrew from the show when they learned what had happened, while Haacke pressed on, staging the installation at Cologne’s Galerie Paul Maenz, with a reproduction standing in for Manet’s painting. (Daniel Buren tried to insert part of Haacke’s project into his own contribution to PROJEKT ’74, but the organizers covered it up.)

As Haacke recounts in a text he later wrote, which has since been reprinted in his collected writings, the censorship of the project hinged on the panel about Hermann J. Abs, the chairman of the Wallraf-Richartz’s Association of the Friends of the Museum, who had been instrumental in acquiring Manet’s painting for the museum. Abs had an ugly past: he had worked high-up at Deutsche Bank from 1938 to 1945, and had reportedly been involved in the Nazis’ “Aryanization” of banking. He continued to play an influential role in the German economy after the war, and was a powerful figure in the cultural landscape as well. (Abs was not alone in this; despite “de-Nazification” efforts after WWII, many ex-Nazis and sympathizers wound up in positions of influence, having paid little or no price for their complicity in the Holocaust.)

In 2015, on a panel about looted art, Haacke discussed what had motivated him to pursue Manet-PROJEKT ’74, which is now, somewhat ironically, in the collection of Cologne’s Museum Ludwig. “I was interested in the lives of the owners of the Manet painting,” Haacke said, “which is perhaps different from research on the provenance of an artwork, which primarily focuses on ownership and its transfer.” He recounted Abs’s activities during and after the Nazi period, and then concluded: “Except for Manet and Abs, who had solicited donations from German corporations to acquire Bunch of Asparagus for the museum, everyone featured with biographies in my extended provenance were Jewish. Thus the innocent-looking still life had accumulated a heavy crust of history.”

For Further Eating

Ok, after all the Nazi talk, I feel a little sheepish about offering you a German recipe (and one with pork, no less)… but here goes!

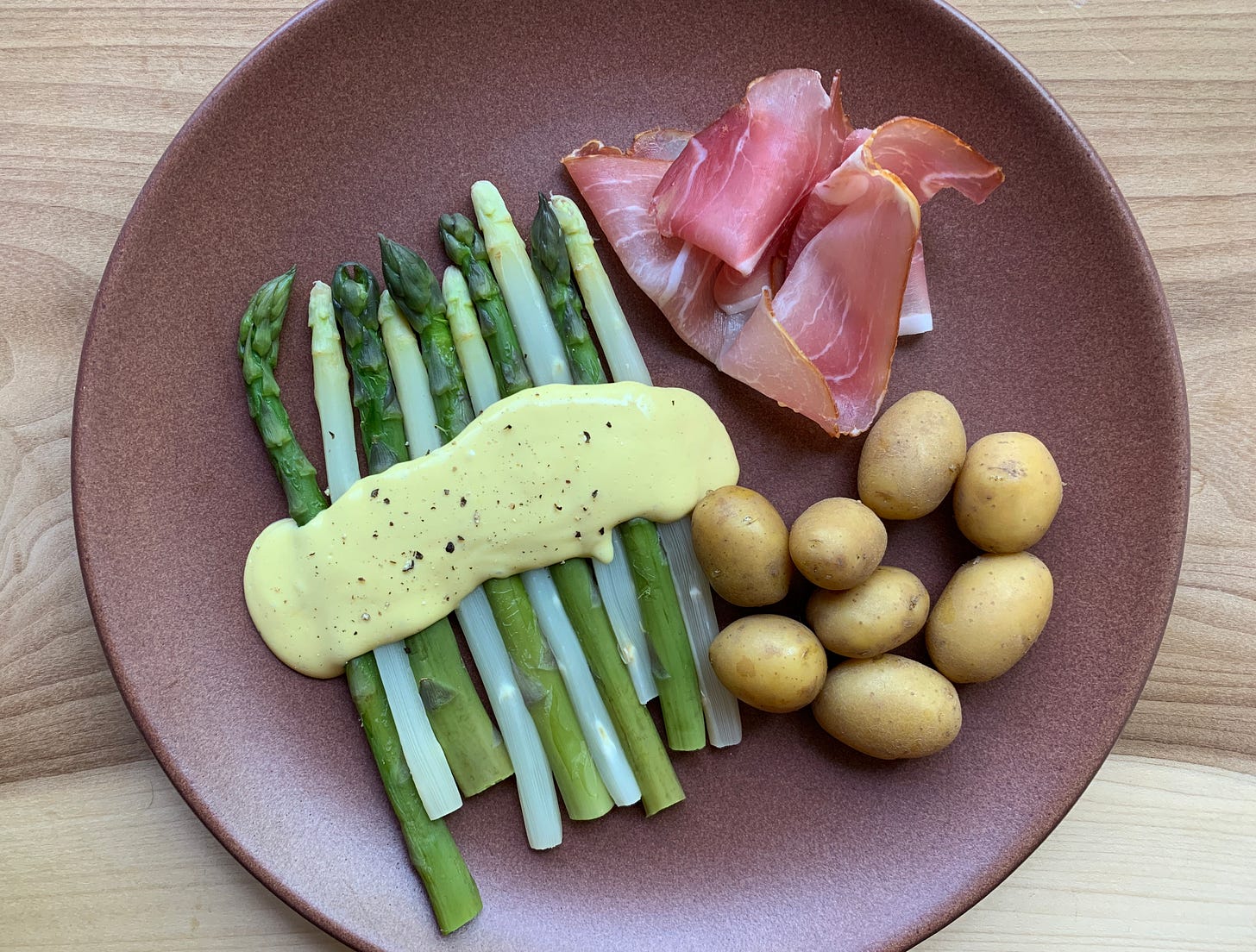

I’ve combined white and green asparagus for this straightforward take on a classic German Spargelzeit meal: boiled asparagus topped with Hollandaise, served with boiled new potatoes and thinly sliced ham. If you’ve never had white asparagus, you’ll find that it can be used in virtually any preparation where you’d normally use green, and on the flip side, if you’ve only got green where you are, just use that!

This recipe works for breakfast, lunch, or dinner, and it comes together quickly, especially if you make your Hollandaise in a blender, a trick that will probably be responsible for my future clogged arteries. (Blender Hollandaise is so magically fast and painless that you can make this for a weeknight dinner, as I did, even with a deliriously hyper toddler underfoot.) If you want some heat, you can add cayenne or hot sauce to the emulsion—but go easy, otherwise you’ll totally overpower the delicacy of the asparagus.

I love this recipe because the asparagus is center stage, but you can vary the proteins and garnishes to suit your preferences: forego the prosciutto altogether or replace it with smoked salmon; top the asparagus with toasted breadcrumbs for a buttery crunch; add a poached egg for extra umami; sprinkle with chopped chives or tarragon. All are good.

Whatever you do, just imagine, when you sit down to eat it, that you’re perched on the velvet banquette of a chic Cologne café, sipping a Rhabarberschorle next to big windows thrown open onto the sidewalk, bathing you in merciful spring warmth.

Asparagus with Hollandaise, Young Potatoes, and Prosciutto

Serves 4

1 bunch white asparagus, peeled from top to bottom and trimmed to remove tough ends

1 bunch green asparagus, trimmed to remove tough ends

1 pound yellow creamer potatoes (or small new potatoes), thoroughly scrubbed

For the hollandaise:

3 large egg yolks

1 tablespoon lemon juice

1 teaspoon Dijon mustard

pinch of salt

1/2 cup (1 stick) unsalted butter

Optional:

8 slices prosciutto

1. Bring medium pot of salted water to boil and add potatoes. Cook until tender, 12 to 15 minutes. Drain and return to the pot to keep warm. (You can optionally toss the potatoes in butter, salt, and pepper, but if your potatoes are anywhere near as delicious as mine were, you’ll want to eat them unadulterated.)

2. While the potatoes are cooking, bring a large pot of salted water to boil for the asparagus. If all of your asparagus is more or less the same thickness, add it all to the pot at one time; if some of your asparagus is considerably thicker, drop those spears in first, wait a few minutes, then add the rest. Boil until just beyond al dente, 5 to 8 minutes—possibly longer, if you’re working with jumbo or colossal asparagus. (Those are, amazingly, technical terms.) Drain thoroughly, and set aside briefly on a paper towel-lined plate.

3. While your potatoes and asparagus are cooking, prep your Hollandaise. Add yolks, lemon juice, salt, and Dijon to a blender. Once you’ve drained your asparagus, melt butter in the microwave or on the stove. Turn blender to high speed for a few seconds, then, with the blender still running at high speed, remove the plug from the lid and add hot butter in a very slow stream until fully incorporated.

4. Divide asparagus spears, potatoes, and prosciutto among four plates. Top asparagus with Hollandaise, season to taste, and serve immediately.

Thank you for reading! If you have feedback, please do share it! You can just hit reply on this email, or click the “Leave a comment” button below to comment publicly.

See you next week!