An Artist's Book of Leaked Recipes

Demetria Glace's droll collection of recipes culled from WikiLeaks, Sony, the Clinton campaign, and more

Welcome to the latest issue of Weekly Special, a food-art newsletter by Andrea Gyorody.

If you’ve landed here but you’re not yet subscribed, you can do that right now:

Before we get to our artwork of the week, a few morsels to share:

Of my various side hustles, my favorite is being the editor of a quarterly online magazine called Digest, published by the LA-based non-profit Active Cultures, which is dedicated to exploring convergences of art and food through programs with artists, chefs, and all sorts of other creatives. The latest edition of Digest, all about sound and food, is out now! This issue—our 10th—boasts essays by music writers Geeta Dayal, Sasha Frere-Jones, Martin Johnson, and Jeff Mao, plus a brand new video by artist Adee Roberson. You’ll find all of that (and more) at the top of the Digest homepage, and if you scroll to the bottom, you can also subscribe to receive future issues in your inbox!

If you enjoyed the issue of Weekly Special on Audrey Flack’s Photorealist painting Strawberry Tart Supreme, you might also enjoy listening to Flack’s very first podcast interview. Her juicy stories about Josef Albers, Alice Neel, Jackson Pollock, and other big names from the 20th-century art world are 100% worth your time.

And! If the Weekly Special issue on Emily Jacir’s Where We Come From piqued your interest, you’ll definitely want to read Aruna d’Souza’s NYT article on the status of the artist’s Bethlehem non-profit Dar Jacir, which is home to an urban farm that was severely damaged in the most recent clashes in the West Bank.

Finally, a programming note: Our big move to LA is happening next week, so Weekly Special will be on break while I supervise movers, fly cross-country with a wiggly toddler, and generally (try not to) freak out. If all goes well, you’ll have a fresh edition of Weekly Special in your inbox in early August.

Now let’s dig in!

This Week’s Special

Demetria Glace

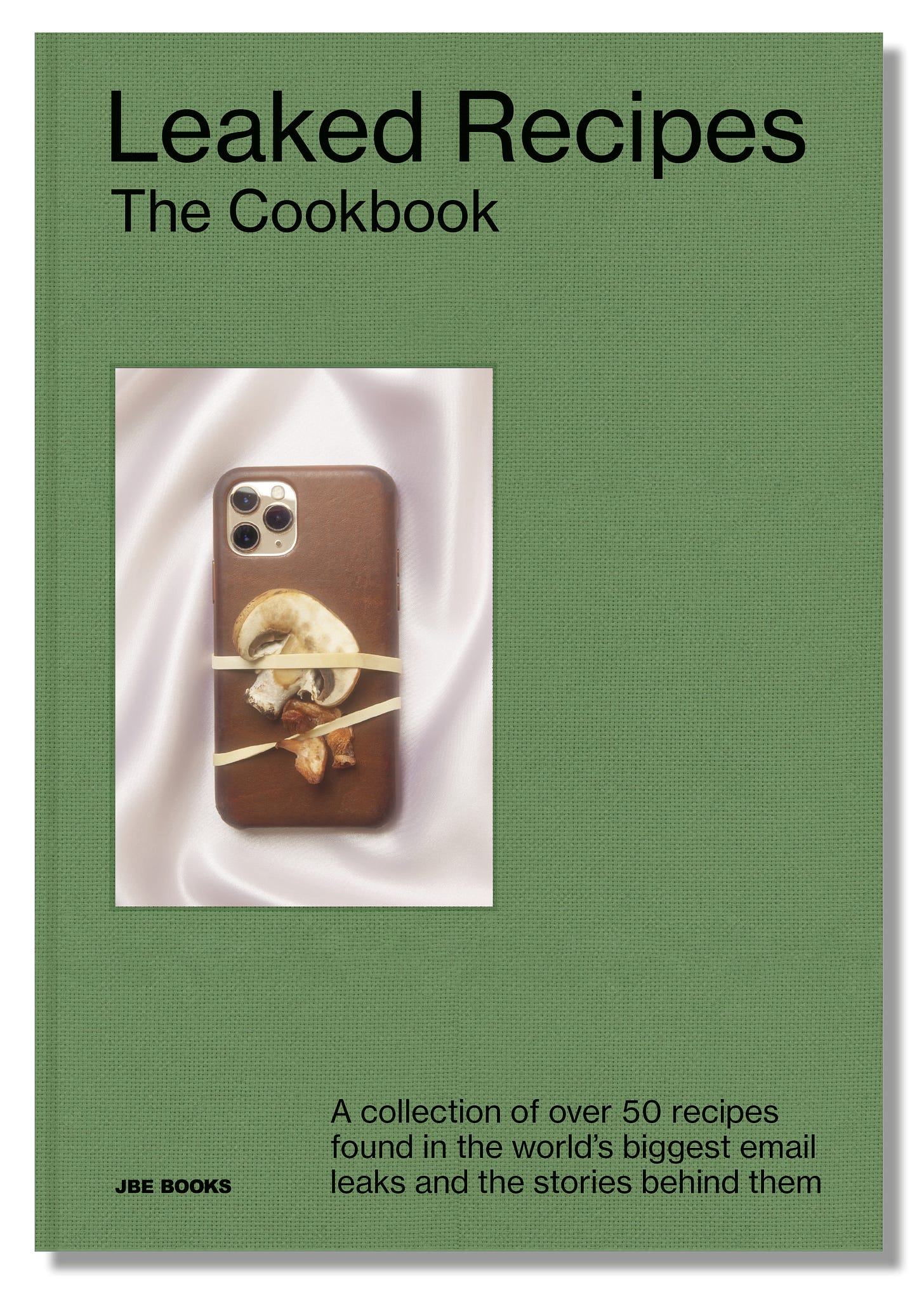

The Leaked Recipes Cookbook, 2021

Artist’s book

Published by JBE Books, Paris

One of my professors in grad school wisely told his teaching assistants that we should never write anything in an email that we wouldn’t want to read aloud during a court proceeding. I rolled my eyes at that advice a decade ago, but I think it’s the absolute best barometer for judging whether you should send an email as originally (and perhaps unwisely) written.

Even though I’ve taken pains to keep emails professional and court-ready (lol, please let that never happen), it would still be my worst nightmare to have my emails hacked and released en masse to the general public. I’m sure 99% of them are dreadfully boring, but there’s that other 1% that are guaranteed to be mortifying, even more so because I likely wouldn’t remember ever having sent them. Reading emails from a decade ago—which happens when I’m in search mode and slip down a Gmail rabbit hole—feels like an out-of-body experience, and not the cool New Age kind.

With all of the hacked emails that have poured onto the interwebs in recent years, though, we should all be ready for the possibility of having our private correspondence uploaded for global access. But unless you’re already famous or powerful—in which case teams of reporters will be pulling all-nighters to turn your most revealing messages into click-bait headlines—your emails, innocuous and cringey alike, will be buried under the avalanche of data that these leaks generate. It’s small comfort, but the average citizen thankfully doesn’t have time to sit around sifting through millions of emails looking for random amusement.

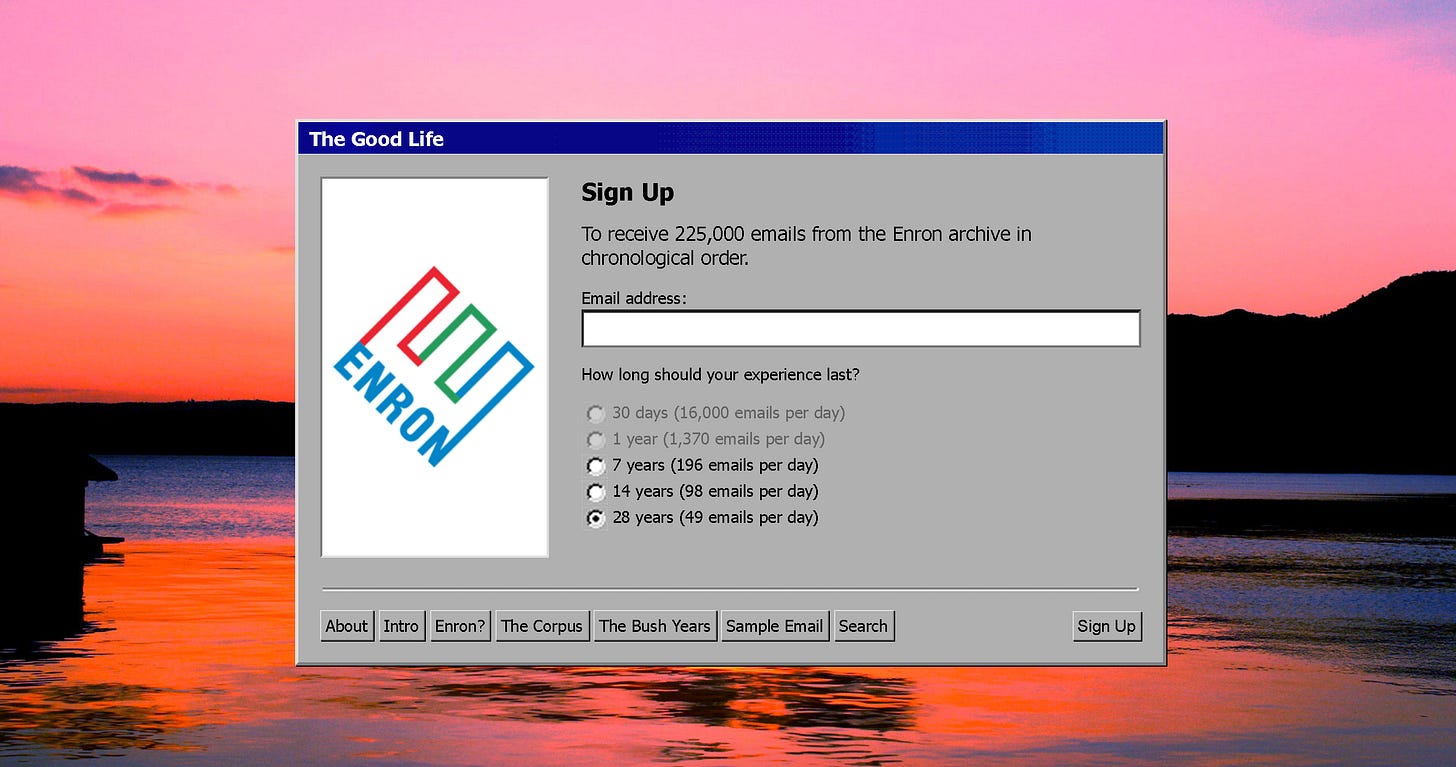

Researcher Gabriela Ivens is not your average citizen. Ivens, who is Head of Open Source Research for the Digital Investigations Lab at Human Rights Watch, signed up several years ago for an art project called The Good Life, which sends emails from the Enron scandal—225,000 of them, in chronological order—to your inbox. The project is still operational; you can opt for a 7-, 14-, or 28-year-long experience, depending on how many emails you want to get a day.

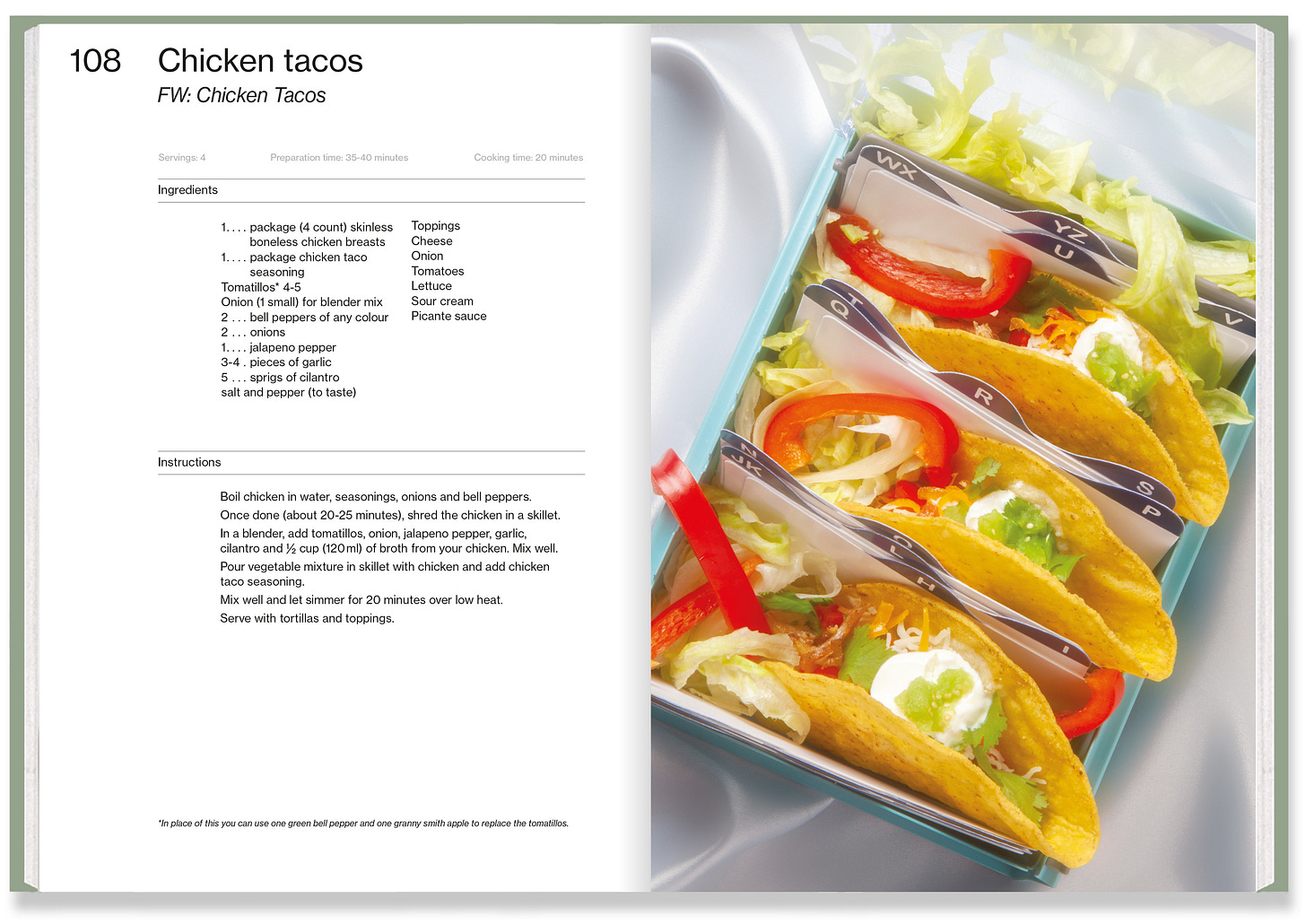

After five months of Enron emails, Ivens got a message with a recipe for Bananas Foster (something she had never heard of), part of a back-and-forth between two Enron staffers arguing about the correct ratio of bananas to liquor. (I shudder to think what ridiculous pedantry lurks in my own emails.) As Ivens has recounted, that Bananas Foster message prompted her to start searching for recipes in other publicly available data breaches—from WikiLeaks, Sony, the Clinton campaign emails, and more. She found quite a few, for everything from chicken tacos to oatmeal raisin cookies, often contextualized with notes on preparation or instructions for how to scale up or down for an upcoming party. Amidst the corruption and petty gossip that dominates most new stories about data hacks, the recipe emails hit a strikingly different note. They were humanizing, endearing even, and offered a revealing window into company culture.

Ivens first presented her growing collection of recipes at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, through a new media program called DocLab, which supports projects that engage novel ways of storytelling. Ivens hosted a series of meals—brunch, high tea, dinners—drawn from the recipes she had gathered, and used the meals for discussions of the rather serious themes the project touches on: privacy, security, conspiracy theories, office culture, the gender dynamics of recipe writing, and the cultural information conveyed by the recipes themselves.

The publishers of the Paris imprint JBE Books came to one of Ivens’ meals, and proposed that she turn the recipes into a cookbook. That idea became The Leaked Recipes Cookbook, released earlier this year under what I surmised to be Ivens’ pen name, Demetria Glace.

[Long aside: I hadn’t realized it was a pen name until I watched Ivens in a YouTube Live conversation, where her fellow guests called her “Gabby” and “Demetria” interchangeably. I’d guess the pen name is aimed at keeping this project separate from her human rights work, though it only took a minor bit of googling to confirm that Glace and Ivens were one and the same. I do appreciate, though, that Ivens’ pen name winks at her subject: Demetria means “follower of Demeter,” goddess of corn and harvest.]

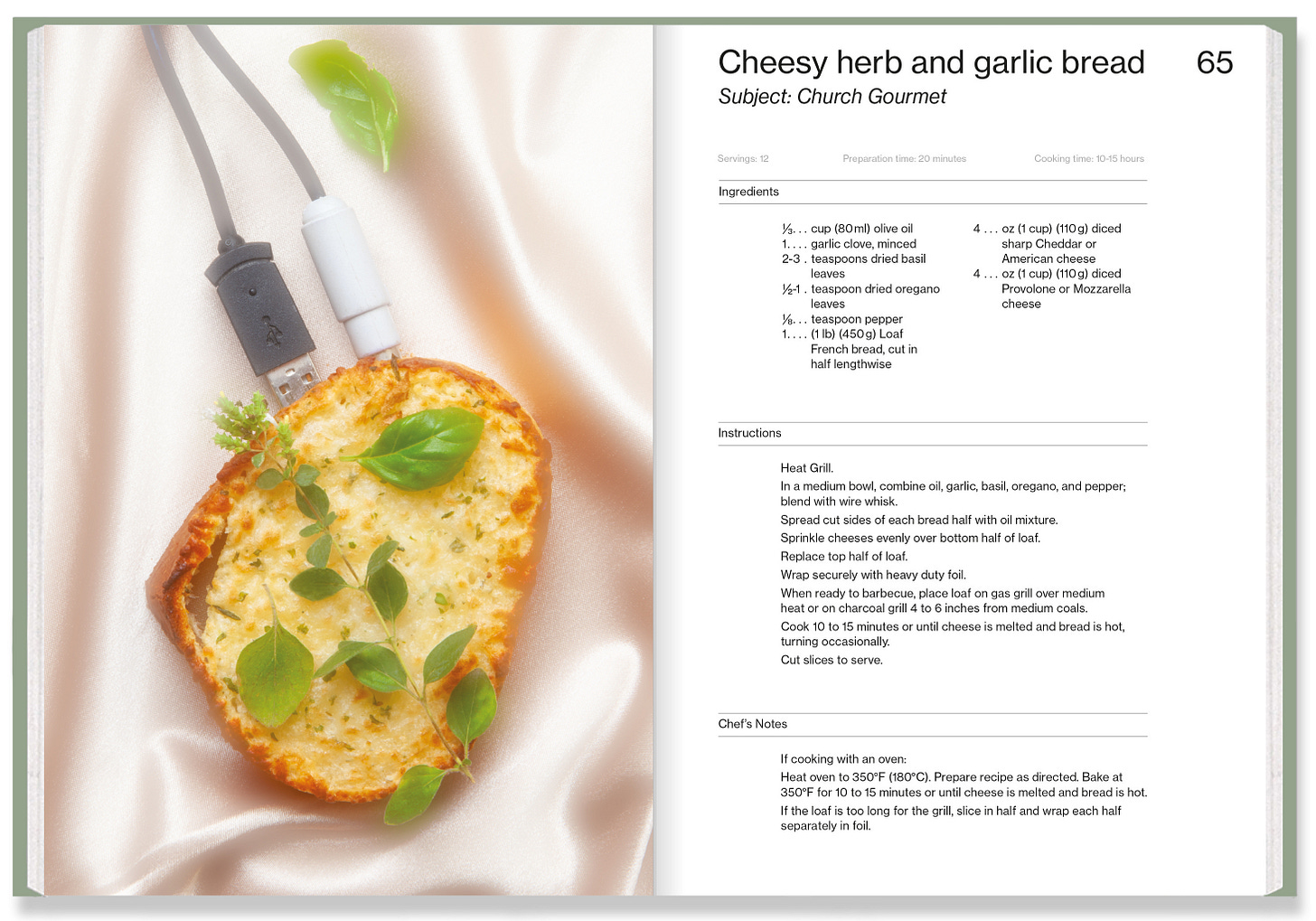

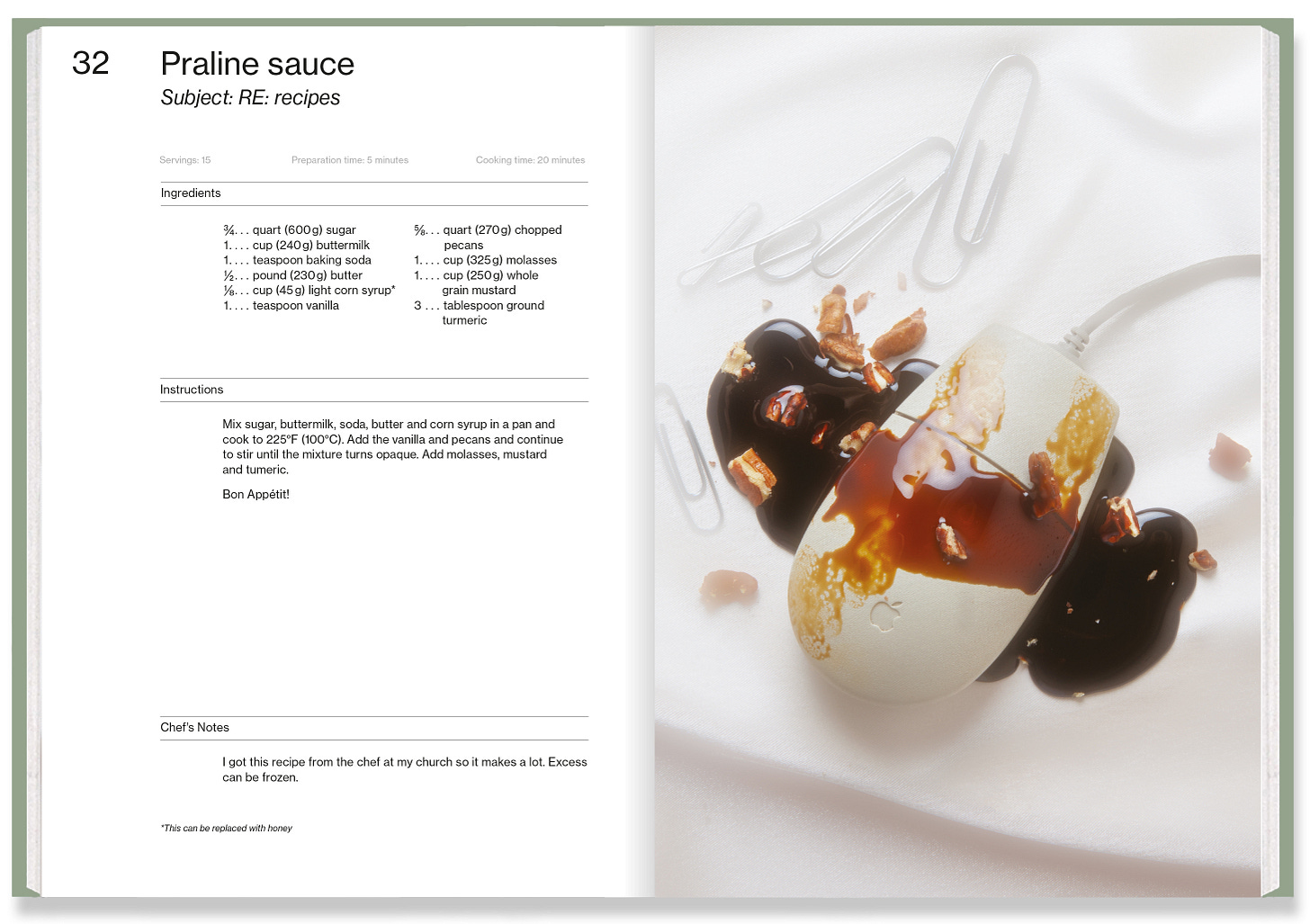

The book contains 52 recipes arranged by course. In order to transform a bunch of emails and attachments into a functional cookbook, Glace standardized the recipes, but kept only the instructions she found in the original emails, even if additional direction might be warranted. She also retained commentary, shifted to a section in each recipe called “Chef’s Notes.” Most of the notes are straightforward, but there were a few tidbits that made me chuckle.

From a recipe for Cheese Dip, sent with the subject line, “Re: more chips in the kitchen for the sludge queso”:

You can go get sharp cheddar blocks, and I’ve tried, believe me, to make organic queso from grass fed cows and it doesn’t turn out as good. It kinda sucks. People don’t like it.

Not gonna argue with that.

Then there’s this, from a recipe for Rib Rub, which left me wondering about the gender identity of the author:

He’s not allowed to share this! Make sure he keeps it a secret between us. Men are like that with their recipes. Oh, make sure you sprinkle a LOT on both sides and press into the ribs. Best to let the spices sit overnight for super tastiness.

What are these classified meat spices, you ask? Here’s a hint: two kinds of salt, some heat, and Tony Chachere’s Original Creole Seasoning.

The secrecy of some of the recipes Glace uncovered—and the irony of those secrets being revealed through a security breach—was part of her interest in the project. The fuzzy ethics of re-leaking the recipes by publishing them in a print cookbook weren’t lost on her: the first recipe that appears in the book is one (for “chili con pumpkin,” which bizarrely calls for squash instead of pumpkin but otherwise sounds delicious) that she found in her own inbox, in an email with the intriguing first line, “Last night was beautiful you lickle trout pizza you.” I don’t speak British English, so I haven’t the first clue what that means, but I appreciate Glace’s gesture of vulnerability at the start of a book of stolen data. I also appreciate her attempts to track down the original recipe senders to ask their permission to publish, and though I’m very nosey and really want to know whose recipes these are (especially if they belong to any of the Clinton crew), it was correct of Glace to redact all identifying information and keep the focus strictly on the recipes and email banter. Of course if you really have to know who sent their co-worker instructions for scalloped potatoes, it’s all on the internet.

I’ll leave you with a few spreads from the book, with playful (and surprisingly sexy?) photos by artist Emilie Baltz. They capture the spirit of the early aughts, with mostly obsolete tech in soft focus, draped over and plugged into equally nostalgic foodstuffs. Seriously: chef’s kiss.

For Further Eating

I’m gonna be frank: a lot of the recipes in The Leaked Recipes Cookbook are downright unappealing. I admit to being intrigued by the repeat mentions of Velveeta®, and on the opposite end of the luxe spectrum, who wouldn’t want pasta with shaved black truffles? But by and large, the church and family recipes of Y2K-era corporate America and recent Democratic Party leadership are ones I could do without.

With our move to LA on the horizon, I was also faced with a pantry that needed pruning, which seemed a task perfectly aligned with the preponderance of canned goods in the Leaked Recipes Cookbook. I decided to let the pantry be my guide, which is how I landed on a very out-of-season recipe for Sweet Pumpkin Dip, from what I’m guessing was the November issue of the Enron company newsletter.

It’s a super simple dessert that comes together in a food processor in less than five minutes—about as much time as I could spare for goofing around between moving tasks. I followed the recipe in the cookbook with two adjustments: I added vanilla to play up the pumpkin pie flavors, and cut down the sugar dramatically, from a whole box of the powdered stuff (which would have rendered this sickly sweet, IMO) to just a few tablespoons. You can easily adjust everything in the recipe to taste, and making it vegan is as simple as subbing vegan cream cheese.

Enjoy some autumn vibes in July!

Sweet Pumpkin Dip

Serves 6-10 as part of a dessert spread

2 packages (approx. 450g) softened cream cheese

1 can (15 oz) pumpkin puree

8 tablespoons powdered sugar (more or less to taste)

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

For dipping: gingersnaps, graham crackers, chocolate bars broken into dippable pieces, whole toasted pecans, sliced apples or pears

1. Add cream cheese, pumpkin puree, cinnamon, nutmeg, and vanilla extract to food processor. Run until smooth, pausing to scrape down sides if necessary.

2. To the pumpkin mixture, add powdered sugar, starting with just a few tablespoons. Run the processor to incorporate, taste, and add more sugar if desired. Once you’ve reached the perfect level of sweetness, run the processor for 2 to 3 minutes to ensure mixture is smooth.

3. Scrape mixture into a container or bowl, cover, and refrigerate for at least an hour to thicken and chill the dip. To serve, place bowl of dip on a serving platter alongside your dipping items of choice.

Growing up, my family pretty regularly ate a Velveeta chip dip as a meal. I miss it and wish I were having it for dinner tonight. Mmm, melted Velveeta!