A Sizzling Quartet of Fried Eggs

Art historian and curator Katia Zavistovski on Vija Celmins' uncommonly good painting "Eggs," from 1964

Welcome to the latest issue of Weekly Special, a food-art newsletter by Andrea Gyorody.

If you’ve landed here but you’re not yet subscribed, you can do that right now:

This week we have a truly fabulous guest post by my dear friend Katia Zavistovski, Assistant Curator of Modern Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Katia is also a newly minted PhD in art history (yay!), with a dissertation that examines 1960s “common object” painting in Los Angeles—a mode of figurative painting that she defines as underscoring materiality, embodiment, and connectedness within a cultural climate increasingly shaped by commodification and alienation.

Below, you’ll find Katia’s rich text on Vija Celmins’ painting Eggs, from 1964. It’s a favorite of mine (along with this contemporaneous painting of a space heater), and it gave me an excuse to escape the box mountain that is my apartment right now to eat a fried egg dish I’ve missed in my time away from LA.

Now let’s dig in!

This Week’s Special

Vija Celmins

Eggs, 1964

Oil on canvas

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego

Museum purchase with funds from George Wick and Ansley I. Graham Trust, Los Angeles in memory of Hope Wick

I was six months pregnant when I began writing the last chapter of my dissertation, which focuses on Vija Celmins’ early paintings of common objects, so it’s probably not surprising that I was especially drawn to Eggs (1964). The work presents a to-scale view of Celmins’ electric skillet, tipped up to showcase a grid of frying eggs, their bright yellow yolks punctuating the otherwise dim palette that dominates the composition. The dish doesn’t look particularly appetizing—it appears more somber than savory—but the painting holds my attention nonetheless. The perspective and true-to-life size of the appliance elicits a relational encounter with the work, calling to mind the familiar experience of watchfully standing over a pan of eggs, waiting for them to cook exactly to one’s liking (and the feeling of mild vexation when a yolk breaks, like the one at the bottom right of Celmins’ pan).

Eggs are an obvious symbol of origins and creation, which is germane. The painting is part of the series that marked the beginning of Celmins’ career, made when she was a graduate student at UCLA. Abandoning the large, gestural manner of painting in the vein of Abstract Expressionism that she had been taught in school, in 1964 she instead focused her attention on mundane foods and sundry items that inhabited her studio: among them her portable skillet, a bowl of soup, her desk lamp, and her shoes. (Only the runny yolk in Eggs—a small splash of unbounded pigment—offers a slight nod toward an expressively abstract gesture.) “I was going back to what I thought was this basic, stupid painting,” she recalled. “You know, there’s the surface, there’s me, there’s my hand, there’s my eye, I paint. I don’t embellish anymore, I don’t compose, and I don’t jazz up the color.”

Like each work in the series, Eggs features an isolated object in the center of nebulous surrounds, a predominantly gray tonality, and a deadpan mode of address. The image couldn’t be more straightforward, and yet there is something discernibly uncanny about it; the longer one looks at the work, the less fixed its subject seems to be. The eggs resemble googly eyeballs gaping at us inquisitively, and an atmosphere of precariousness pervades the scene. The broken yolk contributes a sense of vulnerability, and the skillet, tilted forward and weighed down by its temperature control and power cord, appears as though it might slide down the picture plane.

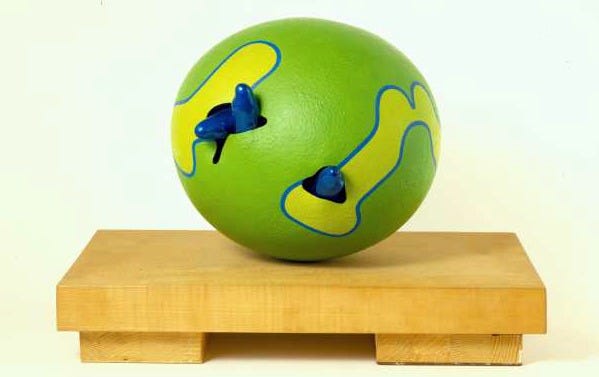

Even Celmins’ use of gray—neutral as it may be—feels incongruous, especially in the context of 1960s Southern California. Celmins painted Eggs shortly after moving into a storefront studio in Venice Beach, which at the time was a vibrant art community and a center for the development of West Coast strains of Pop and Minimalism known as Cool School and Finish Fetish. Celmins was one of very few women artists working in Venice, however, and although she made lasting friendships with neighboring artists, including Robert Irwin, Ken Price, and Doug Wheeler, she developed her practice in relative isolation from the patently male-dominated art scene (a scene that was epitomized, for instance, by the 1964 Ferus Gallery exhibition The Studs). Celmins’ sunny-side-up eggs wryly allude to LA, but the painting shows no glimmer of sunlight streaming through the windows of her Venice studio, and none of the luminosity and gloss that characterized work by her peers. Take Price’s contemporaneous “Eggs,” a series of small ovoid clay sculptures painted with iridescent acrylics and automotive lacquer in garish hues. As in S. L. Green (1963), phallic forms poke through the ceramic “shells,” exhibiting an almost violent eroticism in stark contrast to Celmins’ subdued, introspective take on the subject.

The ashen palette of Celmins’ early work became a hallmark of her practice over the following 50-plus years. Gray is often used to communicate objective neutrality; as Gerhard Richter said about his own work from the 1960s, the color “evokes neither feelings nor associations.” But for Celmins, gray had deep-seated personal meaning. About developing her paintings of ordinary objects, she explained: “I decided that I had to connect with myself. That was a big thing… I began to plumb myself… I began to find things… things that were really somehow a part of me. I mean probably the whole set of grays that I love, especially in this work, you know. I’m from a gray land, Latvia. I’m not from California.”

Celmins moved to Los Angeles in 1962 from her adoptive hometown of Indianapolis, but she was born in Riga, Latvia, in 1938—on the eve of World War II. Over the following several years, Soviet and Nazi troops battled for control over the Baltic region, and in 1944 Celmins and her family fled their native country. They made their way to Germany in the midst of heavy bombing, and were eventually placed in a refugee camp in Esslingen, where they lived for two years before emigrating to the United States when Celmins was 10 years old.

Celmins references her childhood in much of her 1960s oeuvre (most explicitly in her grisaille paintings of WWII-era military planes). In the case of her 1964 body of work, many of the objects she portrayed convey dislocation—signifying her experience as an émigré as well as her more recent move from Indianapolis to LA. All of the household appliances she depicted are portable—an electric skillet and a hot plate rather than a stove. Emphasizing the notion of mobility, Celmins varied the placement of her painted objects: in Eggs the cookware is frontal, in Pan she shows it in a more horizontal three-quarter view. This impression of movement, subtle as it may be, accentuates the tactile and intimate quality of the work. In placing her belongings just so on the canvas, Celmins highlights the fact that they are things she used regularly, relied on for sustenance, and handled with care.

More than just this, though, in my reading of these works the objects represent extensions or even analogs of Celmins herself—“things that were really somehow a part of me,” as she put it. The electric cord in Eggs and her other appliance paintings reinforces this embodied relationship. Extending to the bottom edge of the composition, it functions as an umbilical connection that tethers artist, object, and work. As my brilliant friend (and founder of this newsletter) Andrea Gyorody insightfully observed, the wires are akin to the shutter release cables used in photographic self-portraiture. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #10 (1978) comes to mind, part of the artist’s iconic suite of black-and-white photographs in which she pictures herself in the guises of gendered 1950s and ‘60s cinematic stereotypes.

The image shows Sherman crouching on her kitchen floor, grasping a carton of eggs that has fallen out of a torn grocery bag. The shutter cord snakes out from under her jacket at the lower right of the staged scene, revealing—as do Celmins’ paintings from a decade earlier—the agent and subject of the work to be one and the same.

That was delightful, no? If you want to experience more of Katia’s work, you should book a ticket to see LACMA’s recent reinstallation of modern art highlights, co-curated by Katia and Stephanie Barron. It’s PACKED with gems, including a giant comb by Vija Celmins, and it should be up for quite a while as LACMA makes progress on their new building.

For Further Eating

My big plan for this past week was to drive around LA every lunch hour, eating all of my favorite foods that showcase the unctuous beauty of fried eggs: a classic diner breakfast, huevos rancheros, bibimbap, an indulgent restaurant burger, a grain bowl with puffed rice, and a Croque Madame. Alas, life intervened—in the form of a moving truck finally dropping off all of our household items on the same day our toddler learned how to climb out of his crib—so all I got to eat was that Croque Madame.

I’m sure there are other Croques Madame in LA, but I only have eyes (and stomach) for the one at Republique. When I go back to a restaurant I’ve been to a million times after a long hiatus (two-plus years in this case), I always have a slight feeling of dread that it might not be as awesome as I’d remembered. Republique, which was walking distance from my Miracle Mile apartment (circa 2014-16), is one of those spots for me. I’ve had their “Regular Breakfast” so many times that I can truly taste the bacon steak (yes, bacon steak) just by looking at a photo.

On those rare occasions when I didn’t feel like eating a massive slab of bacon, I’d order the Croque Madame, which managed to be satisfyingly rich without being totally nap-inducing. (The big pile of greens helped.)

Friends, I am happy to report that the Republique Croque Madame holds up! Granted, it would take a lot to screw up a ham and cheese sandwich, but this plate sings. The bread is crunchy and buttery all the way through—hearty enough to stand up to oozing cheese and mornay without throwing off the bread-to-filling ratio. It’s a carb and protein and butter bomb, balanced perfectly by the lightly dressed, vinegary butter lettuce.

And that egg! The orange yolk—no filter here!—is just gorgeous, and the whites have a crispy, lacey edge that gives them some bite.

I have to confess something, though: perhaps contrary to the point of a Croque Madame, I don’t cut into the egg while it sits on top of the sandwich. I slide the egg off the bread, carefully cut away and eat just the whites, and then, at the appropriate moment of the meal (can’t say what makes it appropriate, just a strong feeling), I pop the whole yolk in my mouth. There’s no greater egg-eating pleasure, in my not-so-humble opinion, than a yolk that breaks in your mouth instead of all over your plate, where some of it will inevitably be wasted. Unacceptable.

No Yolk Left Behind, amiright? Tell me I’m not alone in that. Or tell me I’m crazy. Share your own egg predilections in the comments!

This one was lovely. Two takeaways:

I am deeply touched by the reflection of impermanence in the electric skillet. Not by my shared experience of displacement, but by my grandmother who lived a life of uncertain safety next to her electric skillet in the same house for decades.

Secondly, while I'm intrigued by this mouth popping egg yoke theory, I'm not sure how it can coexist with my "if you're not licking yolk off your hands as you eat the sandwich, did it even happen" theory.

You're crazy, but maybe brilliant. Eager to test your egg philosophy!